Using the core functions in practice

This post is the third in a series.

In the previous two posts, I described some of the core functions for dealing with generic data types: map, apply, bind, and so on.

In this post, I’ll show how to use these functions in practice, and will explain the difference between the so-called “applicative” and “monadic” styles.

Here’s a list of shortcuts to the various functions mentioned in this series:

- Part 1: Lifting to the elevated world

- Part 2: How to compose world-crossing functions

- Part 3: Using the core functions in practice

- Part 4: Mixing lists and elevated values

- Part 5: A real-world example that uses all the techniques

- Part 6: Designing your own elevated world

- Part 7: Summary

Now that we have the basic tools for lifting normal values to elevated values and working with cross-world functions, it’s time to start working with them!

In this section, we’ll look at some examples how these functions are actually used.

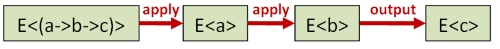

I briefly mentioned earlier that there is a important difference between using apply and bind. Let’s go into this now.

When using apply, you can see that each parameter (E<a>, E<b>) is completely independent of the other. The value of E<b> does not depend on what E<a> is.

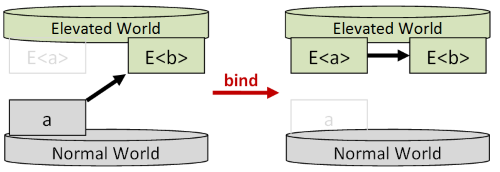

On the other hand, when using bind, the value of E<b> does depend on what E<a> is.

The distinction between working with independent values or dependent values leads to two different styles:

- The so-called “applicative” style uses functions such as

apply,lift, andcombinewhere each elevated value is independent. - The so-called “monadic” style uses functions such as

bindto chain together functions that are dependent on a previous value.

What does that mean in practice? Well, let’s look at an example where you could choose from both approaches.

Say that you have to download data from three websites and combine them. And say that we have an action, say GetURL, that gets the data from a website on demand.

Now you have a choice:

- Do you want to fetch all the URLs in parallel?

If so, treat the

GetURLs as independent data and use the applicative style. - Do you want to fetch each URL one at a time, and skip the next in line if the previous one fails?

If so, treat the

GetURLs as dependent data and use the monadic style. This linear approach will be slower overall than the “applicative” version above, but will also avoid unnecessary I/O. - Does the URL for the next site depend on what you download from the previous site?

In this case, you are forced to use “monadic” style, because each

GetURLdepends on the output of the previous one.

As you can see, the choice between applicative style and monadic style is not clear cut; it depends on what you want to do.

We’ll look at a real implementation of this example in the final post of this series.

but…

It’s important to say that just because you choose a style doesn’t mean it will be implemented as you expect.

As we have seen, you can easily implement apply in terms of bind, so even if you use <*> in your code, the implementation may be proceeding monadically.

In the example above, the implementation does not have to run the downloads in parallel. It could run them serially instead. By using applicative style, you’re just saying that you don’t care about dependencies and so they could be downloaded in parallel.

If you use the applicative style, that means that you define all the actions up front – “statically”, as it were.

In the downloading example, the applicative style requires that you specific in advance which URLs will be visited. And because there is more knowledge up front it means that we can potentially do things like parallelization or other optimizations.

On the other hand, the monadic style means that only the initial action is known up front. The remainder of the actions are determined dynamically, based on the output of previous actions. This is more flexible, but also limits our ability to see the big picture in advance.

Sometimes dependency is confused with order of evaluation.

Certainly, if one value depends on another then the first value must be evaluated before the second value. And in theory, if the values are completely independent (and have no side effects), then they can be evaluated in any order.

However, even if the values are completely independent, there can still be an implicit order in how they are evaluated.

For example, even if the list of GetURLs is done in parallel,

it’s likely that the urls will begin to be fetched in the order in which they are listed, starting with the first one.

And in the List.apply implemented in the previous post, we saw that [f; g] apply [x; y] resulted in [f x; f y; g x; g y] rather than [f x; g x; f y; g y].

That is, all the f values are first, then all the g values.

In general, then, there is a convention that values are evaluated in a left to right order, even if they are independent.

To see how both the applicative style and monadic style can be used, let’s look at an example using validation.

Say that we have a simple domain containing a CustomerId, an EmailAddress, and a CustomerInfo which is a record containing both of these.

type CustomerId = CustomerId of int

type EmailAddress = EmailAddress of string

type CustomerInfo = {

id: CustomerId

email: EmailAddress

}

And let’s say that there is some validation around creating a CustomerId. For example, that the inner int must be positive.

And of course, there will be some validation around creating a EmailAddress too. For example, that it must contain an “@” sign at least.

How would we do this?

First we create a type to represent the success/failure of validation.

type Result<'a> =

| Success of 'a

| Failure of string list

Note that I have defined the Failure case to contain a list of strings, not just one. This will become important later.

With Result in hand, we can go ahead and define the two constructor/validation functions as required:

let createCustomerId id =

if id > 0 then

Success (CustomerId id)

else

Failure ["CustomerId must be positive"]

// int -> Result<CustomerId>

let createEmailAddress str =

if System.String.IsNullOrEmpty(str) then

Failure ["Email must not be empty"]

elif str.Contains("@") then

Success (EmailAddress str)

else

Failure ["Email must contain @-sign"]

// string -> Result<EmailAddress>

Notice that createCustomerId has type int -> Result<CustomerId>, and createEmailAddress has type string -> Result<EmailAddress>.

That means that both of these validation functions are world-crossing functions, going from the normal world to the Result<_> world.

Since we are dealing with world-crossing functions, we know that we will have to use functions like apply and bind, so let’s define them for our Result type.

module Result =

let map f xResult =

match xResult with

| Success x ->

Success (f x)

| Failure errs ->

Failure errs

// Signature: ('a -> 'b) -> Result<'a> -> Result<'b>

// "return" is a keyword in F#, so abbreviate it

let retn x =

Success x

// Signature: 'a -> Result<'a>

let apply fResult xResult =

match fResult,xResult with

| Success f, Success x ->

Success (f x)

| Failure errs, Success x ->

Failure errs

| Success f, Failure errs ->

Failure errs

| Failure errs1, Failure errs2 ->

// concat both lists of errors

Failure (List.concat [errs1; errs2])

// Signature: Result<('a -> 'b)> -> Result<'a> -> Result<'b>

let bind f xResult =

match xResult with

| Success x ->

f x

| Failure errs ->

Failure errs

// Signature: ('a -> Result<'b>) -> Result<'a> -> Result<'b>

If we check the signatures, we can see that they are exactly as we want:

maphas signature:('a -> 'b) -> Result<'a> -> Result<'b>retnhas signature:'a -> Result<'a>applyhas signature:Result<('a -> 'b)> -> Result<'a> -> Result<'b>bindhas signature:('a -> Result<'b>) -> Result<'a> -> Result<'b>

I defined a retn function in the module to be consistent, but I don’t bother to use it very often. The concept of return is important,

but in practice, I’ll probably just use the Success constructor directly. In languages with type classes, such as Haskell, return is used much more.

Also note that apply will concat the error messages from each side if both parameters are failures.

This allows us to collect all the failures without discarding any. This is the reason why I made the Failure case have a list of strings, rather than a single string.

NOTE: I’m using string for the failure case to make the demonstration easier. In a more sophisticated design I would list the possible failures explicitly.

See my functional error handling talk for more details.

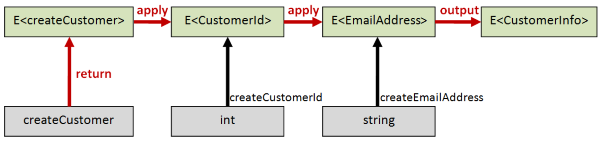

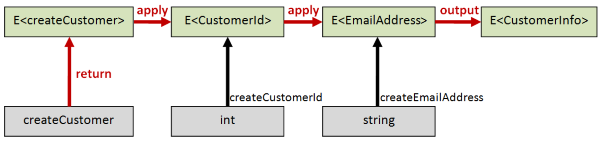

Now that we have the domain and the toolset around Result, let’s try using the applicative style to create a CustomerInfo record.

The outputs of the validation are already elevated to Result, so we know we’ll need to use some sort of “lifting” approach to work with them.

First we’ll create a function in the normal world that creates a CustomerInfo record given a normal CustomerId and a normal EmailAddress:

let createCustomer customerId email =

{ id=customerId; email=email }

// CustomerId -> EmailAddress -> CustomerInfo

Note that the signature is CustomerId -> EmailAddress -> CustomerInfo.

Now we can use the lifting technique with <!> and <*> that was explained in the previous post:

let (<!>) = Result.map

let (<*>) = Result.apply

// applicative version

let createCustomerResultA id email =

let idResult = createCustomerId id

let emailResult = createEmailAddress email

createCustomer <!> idResult <*> emailResult

// int -> string -> Result<CustomerInfo>

The signature of this shows that we start with a normal int and string and return a Result<CustomerInfo>

Let’s try it out with some good and bad data:

let goodId = 1

let badId = 0

let goodEmail = "test@example.com"

let badEmail = "example.com"

let goodCustomerA =

createCustomerResultA goodId goodEmail

// Result<CustomerInfo> =

// Success {id = CustomerId 1; email = EmailAddress "test@example.com";}

let badCustomerA =

createCustomerResultA badId badEmail

// Result<CustomerInfo> =

// Failure ["CustomerId must be positive"; "Email must contain @-sign"]

The goodCustomerA is a Success and contains the right data, but the badCustomerA is a Failure and contains two validation error messages. Excellent!

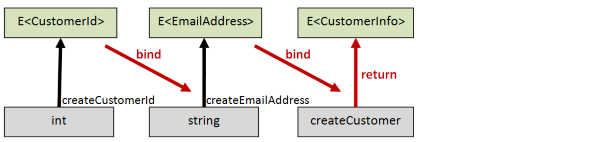

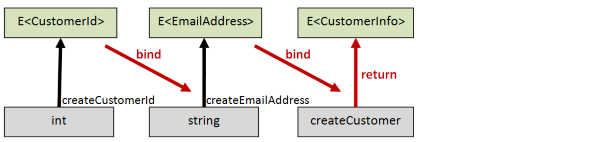

Now let’s do another implementation, but this time using monadic style. In this version the logic will be:

- try to convert an int into a

CustomerId - if that is successful, try to convert a string into a

EmailAddress - if that is successful, create a

CustomerInfofrom the customerId and email.

Here’s the code:

let (>>=) x f = Result.bind f x

// monadic version

let createCustomerResultM id email =

createCustomerId id >>= (fun customerId ->

createEmailAddress email >>= (fun emailAddress ->

let customer = createCustomer customerId emailAddress

Success customer

))

// int -> string -> Result<CustomerInfo>

The signature of the monadic-style createCustomerResultM is exactly the same as the applicative-style createCustomerResultA but internally it is doing something different,

which will be reflected in the different results we get.

let goodCustomerM =

createCustomerResultM goodId goodEmail

// Result<CustomerInfo> =

// Success {id = CustomerId 1; email = EmailAddress "test@example.com";}

let badCustomerM =

createCustomerResultM badId badEmail

// Result<CustomerInfo> =

// Failure ["CustomerId must be positive"]

In the good customer case, the end result is the same, but in the bad customer case, only one error is returned, the first one.

The rest of the validation was short circuited after the CustomerId creation failed.

This example has demonstrated the difference between applicative and monadic style quite well, I think.

- The applicative example did all the validations up front, and then combined the results. The benefit was that we didn’t lose any of the validation errors. The downside was we did work that we might not have needed to do.

- On the other hand, the monadic example did one validation at a time, chained together. The benefit was that we short-circuited the rest of the chain as soon as an error occurred and avoided extra work. The downside was that we only got the first error.

Now there is nothing to say that we can’t mix and match applicative and monadic styles.

For example, we might build a CustomerInfo using applicative style, so that we don’t lose any errors,

but later on in the program, when a validation is followed by a database update,

we probably want to use monadic style, so that the database update is skipped if the validation fails.

Finally, let’s build a computation expression for these Result types.

To do this, we just define a class with members called Return and Bind, and then we create an instance of that class, called result, say:

module Result =

type ResultBuilder() =

member this.Return x = retn x

member this.Bind(x,f) = bind f x

let result = new ResultBuilder()

We can then rewrite the createCustomerResultM function to look like this:

let createCustomerResultCE id email = result {

let! customerId = createCustomerId id

let! emailAddress = createEmailAddress email

let customer = createCustomer customerId emailAddress

return customer }

This computation expression version looks almost like using an imperative language.

Note that F# computation expressions are always monadic, as is Haskell do-notation and Scala for-comprehensions. That’s not generally a problem, because if you need applicative style it is very easy to write without any language support.

In practice, we often have a mish-mash of different kinds of values and functions that we need to combine together.

The trick for doing this is to convert all them to the same type, after which they can be combined easily.

Let’s revisit the previous validation example, but let’s change the record so that it has an extra property, a name of type string:

type CustomerId = CustomerId of int

type EmailAddress = EmailAddress of string

type CustomerInfo = {

id: CustomerId

name: string // New!

email: EmailAddress

}

As before, we want to create a function in the normal world that we will later lift to the Result world.

let createCustomer customerId name email =

{ id=customerId; name=name; email=email }

// CustomerId -> String -> EmailAddress -> CustomerInfo

Now we are ready to update the lifted createCustomer with the extra parameter:

let (<!>) = Result.map

let (<*>) = Result.apply

let createCustomerResultA id name email =

let idResult = createCustomerId id

let emailResult = createEmailAddress email

createCustomer <!> idResult <*> name <*> emailResult

// ERROR ~~~~

But this won’t compile! In the series of parameters idResult <*> name <*> emailResult one of them is not like the others.

The problem is that idResult and emailResult are both Results, but name is still a string.

The fix is just to lift name into the world of results (say nameResult) by using return, which for Result is just Success.

Here is the corrected version of the function that does work:

let createCustomerResultA id name email =

let idResult = createCustomerId id

let emailResult = createEmailAddress email

let nameResult = Success name // lift name to Result

createCustomer <!> idResult <*> nameResult <*> emailResult

The same trick can be used with functions too.

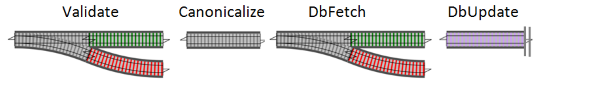

For example, let’s say that we have a simple customer update workflow with four steps:

- First, we validate the input. The output of this is the same kind of

Resulttype we created above. Note that this validation function could itself be the result of combining other, smaller validation functions usingapply. - Next, we canonicalize the data. For example: lowercasing emails, trimming whitespace, etc. This step never raises an error.

- Next, we fetch the existing record from the database. For example, getting a customer for the

CustomerId. This step could fail with an error too. - Finally, we update the database. This step is a “dead-end” function – there is no output.

For error handling, I like to think of there being two tracks: a Success track and a Failure track. In this model, an error-generating function is analogous to a railway switch (US) or points (UK).

The problem is that these functions cannot be glued together; they are all different shapes.

The solution is to convert all of them to the same shape, in this case the two-track model with success and failure on different tracks. Let’s call this Two-Track world!

Each original function, then, needs to be elevated to Two-Track world, and we know just the tools that can do this!

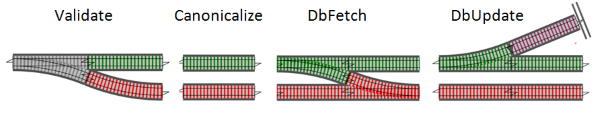

The Canonicalize function is a single track function. We can turn it into a two-track function using map.

The DbFetch function is a world-crossing function. We can turn it into a wholly two-track function using bind.

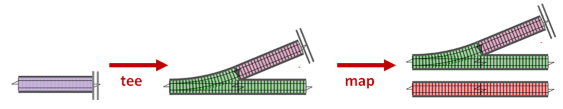

The DbUpdate function is more complicated. We don’t like dead-end functions, so first we need to transform it to a function where the data keeps flowing.

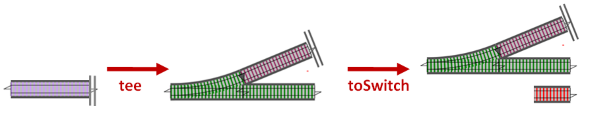

I’ll call this function tee. The output of tee has one track in and one track out, so we need to convert it to a two-track function, again using map.

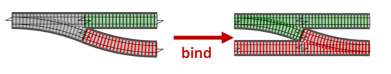

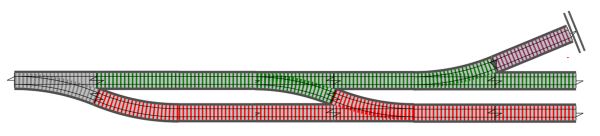

After all these transformations, we can reassemble the new versions of these functions. The result looks like this:

And of course, these functions can now be composed together very easily, so that we end up with a single function looking like this, with one input and a success/failure output:

This combined function is yet another world-crossing function of the form a->Result<b>, and so it in turn can be used as a component part of a even bigger function.

For more examples of this “elevating everything to the same world” approach, see my posts on functional error handling and threading state.

There is an alternative world which can be used as a basic for consistency which I will call “Kleisli” world, named after Professor Kleisli – a mathematician, of course!

In Kleisli world everything is a cross-world function! Or, using the railway track analogy, everything is a switch (or points).

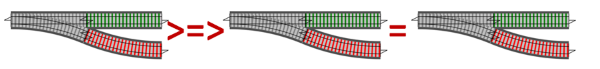

In Kleisli world, the cross-world functions can be composed directly,

using an operator called >=> for left-to-right composition or <=< for right-to-left composition.

Using the same example as before, we can lift all our functions to Kleisli world.

- The

ValidateandDbFetchfunctions are already in the right form so they don’t need to be changed. - The one-track

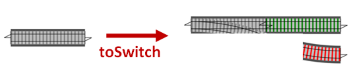

Canonicalizefunction can be lifted to a switch just by lifting the output to a two-track value. Let’s call thistoSwitch.

- The tee-d

DbUpdatefunction can be also lifted to a switch just by doingtoSwitchafter the tee.

Once all the functions have been lifted to Kleisli world, they can be composed with Kleisli composition:

Kleisli world has some nice properties that Two-Track world doesn’t but on the other hand, I find it hard to get my head around it! So I generally stick to using Two-Track world as my foundation for things like this.

In this post, we learned about “applicative” vs “monadic” style, and why the choice could have an important effect on which actions are executed, and what results are returned.

We also saw how to lift different kinds values and functions to a consistent world so that our functions can be composed more easily.

In the next post we’ll look at a common problem: working with lists of elevated values.

Twitter

Twitter