Dependency injection using the Reader monad

In this series, we are looking at six different approaches to dependency injection.

- In the first post, we looked at “dependency retention” (inlining the dependencies) and “dependency rejection” (keeping I/O at the edges of your implementation).

- In the second post, we looked at injecting dependencies as standard function parameters.

- In this post, we’ll look at dependency handling using classic OO-style dependency injection and the FP equivalent: the Reader monad

In the previous post, I briefly discussed the logging problem. How can you access a dependency from deep inside your domain?

Here’s an example of the problem. Code which compares two strings (which is pure), but also needs a logger. The obvious solution is to pass a ILogger as a parameter.

let compareTwoStrings (logger:ILogger) str1 str2 =

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Starting"

let result =

if str1 > str2 then

Bigger

else if str1 < str2 then

Smaller

else

Equal

logger.Info (sprintf "compareTwoStrings: result=%A" result)

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Finished"

result

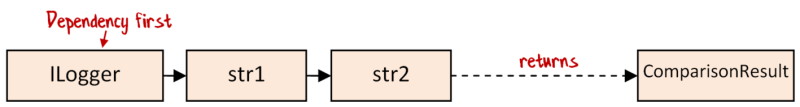

As we saw above, the standard way to pass dependencies as a parameter is to put them first, so that they can be partially applied. If we made a diagram from the function signature for the code above, it would look something like this:

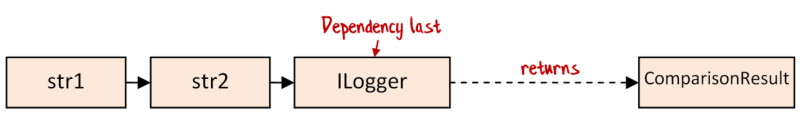

But what if we passed any dependencies in last? So that the function signature looked like this:

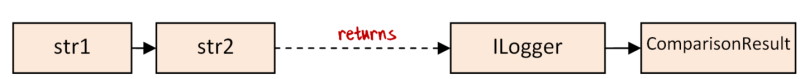

What’s the benefit of doing this? The benefit is that you can reinterpret that signature so that it looks like this:

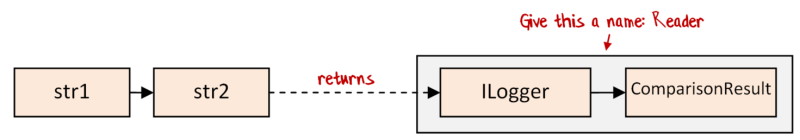

So instead of our function returning the original ComparisonResult, it returns a function, a function with the signature ILogger -> ComparisonResult.

What we are doing is delaying the need for the dependency. The function is now saying: I’ll do my work assuming the dependency is available, and then later, you will actually give me that dependency.

If you think about it, this is exactly how traditional OO-style dependency injection is done.

- First, you implement a class and its methods assuming that a dependency will be available later.

- Later on, you pass in the actual dependency when you construct the class.

Here’s an example of a class definition in F#

// logger passed in via the constructor

type StringComparisons(logger:ILogger) =

member __.CompareTwoStrings str1 str2 =

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Starting"

let result = ...

logger.Info (sprintf "compareTwoStrings: result=%A" result)

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Finished"

result

And here’s the class being constructed with a logger instance later:

// create the logger

let logger : ILogger = defaultLogger

// construct the class

let stringComparisons = StringComparisons logger

// call the method

stringComparisons.CompareTwoStrings "a" "b"

Interestingly, in F#, the call to the class constructor – StringComparisons logger – looks just like a function call, passing in the logger as the “last” parameter to the class.

What’s the FP version of “passing in the dependencies later”? As we saw above, it simply means returning a function where the function has an ILogger parameter which will be provided later.

Here’s the compareTwoStrings function, but now with the ILogger dependency as the last parameter:

let compareTwoStrings str1 str2 (logger:ILogger) =

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Starting"

let result = ...

logger.Info (sprintf "compareTwoStrings: result=%A" result)

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Finished"

result

And here’s exactly the same function, reinterpreted such that the return value is a ILogger -> ComparisonResult function.

let compareTwoStrings str1 str2 =

fun (logger:ILogger) ->

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Starting"

let result = ...

logger.Info (sprintf "compareTwoStrings: result=%A" result)

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Finished"

result

This turns out to be a very common pattern in FP, so much so that it has a name: the “Reader monad” or the “Environment monad”.

Using the dreaded m-word makes it sounds complicated, but all we are doing is giving a name to a function which has some sort of context or environment as the parameter. In our case, the environment is the ILogger dependency.

To make it easier to use, we will wrap this function up in a generic type, like so:

type Reader<'env,'a> = Reader of action:('env -> 'a)

You can understand this as: a Reader contains a function that takes some environment 'env as the input, and returns a value 'a

If we tweak our code to wrap the returned function in the Reader type, then our new implementation looks like this:

let compareTwoStrings str1 str2 :Reader<ILogger,ComparisonResult> =

fun (logger:ILogger) ->

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Starting"

let result = ...

logger.Info (sprintf "compareTwoStrings: result=%A" result)

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Finished"

result

|> Reader // <------------------ NEW!!!

Notice that the return type has now changed from ILogger -> ComparisonResult to Reader<ILogger,ComparisonResult>

Ok, so why we have done all this extra work? Why bother?

The reason is that the Reader type can be composed, transformed and chained in just the same way that the Option or Result or List or Async types can be.

If you are familiar with my Railway Oriented Programming post, you can use the same patterns to chain “Reader-returning” functions as you do for chaining “Result-returning” functions. You can write a map function for it, and a bind/flatMap function for it, and so on. It’s a monad!

Here’s a module with some useful Reader functions:

module Reader =

/// Run a Reader with a given environment

let run env (Reader action) =

action env // simply call the inner function

/// Create a Reader which returns the environment itself

let ask = Reader id

/// Map a function over a Reader

let map f reader =

Reader (fun env -> f (run env reader))

/// flatMap a function over a Reader

let bind f reader =

let newAction env =

let x = run env reader

run env (f x)

Reader newAction

If we have a bind function, we can easily create a computation expression as well. Here’s how we can define a basic computation expression for Reader.

type ReaderBuilder() =

member __.Return(x) = Reader (fun _ -> x)

member __.Bind(x,f) = Reader.bind f x

member __.Zero() = Reader (fun _ -> ())

// the builder instance

let reader = ReaderBuilder()

We don’t have to use reader computation expressions, but it will often make our life easier if we do.

Let’s look at this how this all plays out in practice. Let’s take our original code from the first post and split it into three parts: reading the strings, comparing the strings, and printing the output.

Here’s compareTwoStrings rewritten to use a reader computation expression:

let compareTwoStrings str1 str2 =

reader {

let! (logger:ILogger) = Reader.ask

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Starting"

let result = ...

logger.Info (sprintf "compareTwoStrings: result=%A" result)

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Finished"

return result

}

It looks very similar to the previous implementations, but there are few things to notice:

- Everything is contained in a

reader {...}computation expression. - The

ILoggerparameter has gone. Instead we can access the environment value (ILoggerin this case) directly usingReader.ask. - Just as in all computation expressions, we can use

let!anddo!to “unpack” the contents of the Reader value. In this case we are usinglet!to unpack theaskReader to get the environment (anILogger). - I’ve added an explicit type annotation to the

let! (logger:ILogger) = Reader.ask. This allows the compiler to infer the type of the reader without me having to explicitly annotate the whole function.

We can do the same thing for the function that reads the strings from the console:

let readFromConsole() =

reader {

let! (console:IConsole) = Reader.ask

console.WriteLn "Enter the first value"

let str1 = console.ReadLn()

console.WriteLn "Enter the second value"

let str2 = console.ReadLn()

return str1,str2

}

This time the ask is annotated with the IConsole type.

But what if we needed two different services though? We could try writing something like this:

let readFromConsole() =

reader {

let! (console:IConsole) = Reader.ask

let! (logger:ILogger) = Reader.ask // error

...

But that would cause a compiler error. This is because the first line implies that the Reader type is Reader<IConsole,_> and the second line implies that the Reader type is Reader<ILogger,_>. These types are not compatible.

There are a couple of different approaches we can use to work around this problem.

In F# we can exploit a trick with inheritance. We can require that the console inherit from IConsole and the logger inherit from ILogger. The compiler will now infer that the Reader type is something that inherits from both IConsole and ILogger. Problem solved!

The easiest way to indicate the inheritance constraint in F# is to use the # symbol in front of a type annotation, like this:

let readFromConsole() =

reader {

let! (console:#IConsole) = Reader.ask

let! (logger:#ILogger) = Reader.ask // OK now!

...

And now the Reader type is inferred without error. The actual inferred type is Reader<'a,...> when 'a :> ILogger and 'a :> IConsole.

Let’s tweak compareTwoStrings in the same way:

let compareTwoStrings str1 str2 =

reader {

let! (logger:#ILogger) = Reader.ask

logger.Debug "Starting"

and we can also implement a function that writes the result:

let writeToConsole (result:ComparisonResult) =

reader {

let! (console:#IConsole) = Reader.ask

match result with

| Bigger ->

console.WriteLn "The first value is bigger"

| Smaller ->

console.WriteLn "The first value is smaller"

| Equal ->

console.WriteLn "The values are equal"

}

Finally, we can combine these three functions, each of which is a Reader-returning function.

First we need to define something that will implement both ILogger and IConsole

type IServices =

inherit ILogger

inherit IConsole

And now we create a computation expression containing all three functions.

let program :Reader<IServices,_> = reader {

let! str1,str2 = readFromConsole()

let! result = compareTwoStrings str1 str2

do! writeToConsole result

}

It’s important to understand that at this point the program has not been run yet. Just like Async values or home made parsers, it has the potential to be run, but we will need to pass in an IServices to actually run it.

Given that we have a default implementation of the console and logger, we can implementation of IServices like this:

let services =

{ new IServices

interface IConsole with

member __.ReadLn() = defaultConsole.ReadLn()

member __.WriteLn str = defaultConsole.WriteLn str

interface ILogger with

member __.Debug str = defaultLogger.Debug str

member __.Info str = defaultLogger.Info str

member __.Error str = defaultLogger.Error str

}

And finally, we can run the whole thing:

Reader.run services program

The inheritance approach is nice but can quickly become unwieldy with lots of methods to implement. This can be reduced by having intermediate interfaces which only have one member. This is covered well in the post by Bartosz Sypytkowski so I won’t cover it here.

Instead let’s look at another approach which does not use inheritance at all.

We start by defining the functions as before, this time each function asks for the exact type it needs, not a subclass. If a function needs more than one service, it asks for a tuple from the environment.

let readFromConsole() =

reader {

// ask for an IConsole,ILogger pair

let! (console:IConsole),(logger:ILogger) = Reader.ask // a tuple

...

return str1,str2

}

let compareTwoStrings str1 str2 =

reader {

// ask for an ILogger

let! (logger:ILogger) = Reader.ask

logger.Debug "compareTwoStrings: Starting"

let result = ...

return result

}

let writeToConsole (result:ComparisonResult) =

reader {

// ask for an IConsole

let! (console:IConsole) = Reader.ask

match result with

...

}

Now if we attempt to compose them in a computation expression, we get lots of errors:

let program_bad = reader {

let! str1, str2 = readFromConsole()

let! result = compareTwoStrings str1 str2 // error

do! writeToConsole result // error

}

The reason is that all the Readers are different types: readFromConsole expects a IConsole * ILogger environment, while compareTwoStrings expects a ILogger environment, and so on.

What we need to do to fix this is to create a “supertype” that can be transformed into any of the desired environments. Here it is:

type Services = {

Logger : ILogger

Console : IConsole

}

Next, we need a way to map from the Services type to the individual sub-environments. I’ll call this withEnv:

/// Transform a Reader's environment from subtype to supertype.

let withEnv (f:'superEnv->'subEnv) reader =

Reader (fun superEnv -> (run (f superEnv) reader))

// The new Reader environment is now "superEnv"

Aside: The type signature for withEnv looks very like the signature for “map”. We’re transforming a Reader<subEnvironment> to a Reader<superEnvironment>, and passing in a mapping function f to do this. Unlike a normal map function, the types in f go in the other direction (superEnv->subEnv rather than subEnv->superEnv). The jargon word for this signature is “contramap”.

Now we can take the Reader that each function returns and transform its environment using Reader.withEnv, as shown below:

let program = reader {

// helper functions to transform the environment

let getConsole services = services.Console

let getLogger services = services.Logger

let getConsoleAndLogger services = services.Console,services.Logger // a tuple

let! str1, str2 =

readFromConsole()

|> Reader.withEnv getConsoleAndLogger

let! result =

compareTwoStrings str1 str2

|> Reader.withEnv getLogger

do! writeToConsole result

|> Reader.withEnv getConsole

}

By using withEnv, we’ve made the code in the computation expression a bit more complicated in exchange for making the implementation of the services much more flexible.

Again, the program has not been run yet. We will need to pass in an Services to actually run it, like this:

let services = {

Console = defaultConsole

Logger = defaultLogger

}

Reader.run services program

For another example of using the Reader monad, see the last post in this series.

The Reader approach is rarely used in F# but is commonly used in Haskell and FP-style Scala. Some good posts on using it in F# are by Carsten König and Matthew Podwysokci .

Both OO-style dependency injection and FP-style Readers rely on passing dependencies as the last step, after the code has already been developed.

Which one is better, and when should they be used?

First, if you are interacting with a C# framework that does dependency injection (such as ASP.NET) your life will be much easier if you design your F# code to be compatible with that approach.

Otherwise, using the Reader monad has lots of nice features: it eliminates the ugly dependency parameters used in the “dependency parameterization” approach discussed in the previous post, it is more composable than OO-style dependency injection, and you have standard tools like map and bind to transform and adapt them.

But it’s not all good news. The Reader monad has the same major issue that all monad-centric approaches do: it’s hard to mix and match them with other types.

For example, if you want to return a Result as well as a Reader, you can’t just quickly integrate the two types. And if you want to add Async to the design as well, it can get even more complicated. Yes, there is a solution to this, but it is all too easy to become bogged down in “Type Tetris”, spending too much time trying to get the types to match up. In fact, for the “edge” part of your code, which is heavily I/O, I would not use Reader at all because of the pain of these mismatches. Save the Reader approach for injecting dependencies like loggers into your pure code.

To summarize, I think that Readers are a good tool to have in your toolbox, especially if you are passionate about keeping your code pure, Haskell style. But F# is not Haskell, and so I think that using Reader by default is overkill. I’d probably reach first for one of the other approaches discussed in this series, depending on the circumstances.

We are not done yet! In the next post, we’ll look at one more approach to managing dependencies: the interpreter pattern.

The source code for this post is available at this gist.

Twitter

Twitter