Serializing your domain model

This post is part of the F# Advent Calendar in English 2017 project. Check out all the other great posts there! And special thanks to Sergey Tihon for organizing this.

In most discussions of functional design principles, we focus on implementing business workflows as pure functions with inputs and outputs. But where do these inputs come from? And where do the outputs go? They come from, or go to, some infrastructure that lives outside our workflow – a message queue, a web request, and so on.

This infrastructure has no understanding of our particular domain, and therefore we must convert types in our domain model into something that the infrastructure does understand, such as JSON, XML, or a binary format like protobuf.

We frequently need some way of keeping track of any internal state as well. Again, we will probably use an external service for this, such as a database.

It’s clear then that an important aspect of working with external infrastructure is the ability to convert the types in our domain model into things that can be serialized and deserialized easily.

In this post, we’ll look at how to do just this; we’ll see how to design types that can be serialized, and then we’ll see how to convert our domain objects to and from these intermediate types.

Here’s an outline of this post:

- Transferring data between contexts

- DTOs as contracts between bounded contexts

- A complete serialization example

- Guidelines for translating algebraic data types to DTOs

Let’s start with thinking about how serialization fits in with a functional domain model.

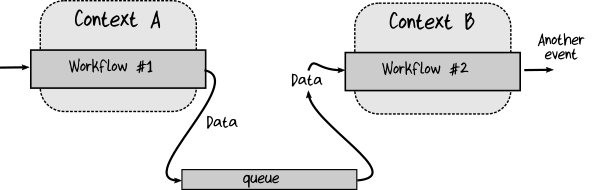

First, we want to ensure that there is a clear boundary between the trusted domain and the untrusted outside world. I’ll follow the domain-driven design convention and call this trusted domain a bounded context. A bit of data (such as a domain event) is generated in one context and then transmitted to another via the infrastructure (e.g. a queue).

The data objects that are passed around may be superficially similar to the objects defined inside the bounded context (which we’ll call Domain Objects), but (normally) they are not the same; they are specifically designed to be serialized and shared as part of the inter-context infrastructure. I’ll call these objects Data Transfer Objects or DTOs (a slight change from the original meaning of the term).

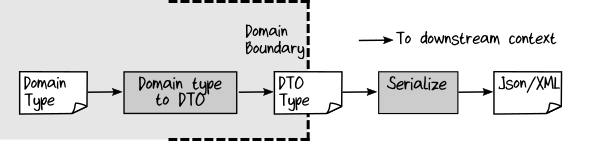

At the boundary of the upstream context then, the domain objects are converted into DTOs, which are in turn serialized into JSON, XML, or some other serialization format:

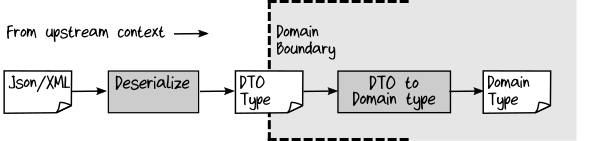

At the downstream context, the process is repeated in the other direction: the JSON or XML is deserialized into a DTO, which in turn is converted into a domain object:

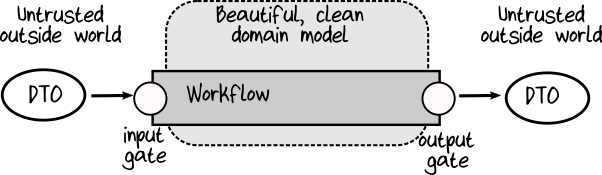

The perimeter of a bounded context acts as a “trust boundary.” Anything inside the bounded context will be trusted and valid, while anything outside the bounded context will be untrusted and might be invalid. Therefore, we will add “gates” at the beginning and end of the workflow which act as intermediaries between the trusted domain and the untrusted outside world.

At the input gate, we will always validate the input to make sure that it conforms to the constraints of the domain model. For example, say that a certain property of a domain object must be non-null and less than 50 characters. The incoming DTO will have no such constraints and could contain anything, but after validation at the input gate, we can be sure that the domain object is valid. And, because the data is immutable, we never have to revalidate it again in the domain: no defensive programming needed. On the other hand, if the validation fails, then the rest of the workflow is bypassed and an error is generated.

Note that we want the deserialization step itself to be as clean as possible, That means that the deserialization into a DTO should always succeed unless the underlying data is corrupt somehow. Any kind of domain specific validation (such as validating integer bounds or checking that a string length is valid) should be done in the “DTO to Domain type” conversion step inside the domain where we understand the domain and have better control of error handling.

The job of the output gate is different. Its job is to ensure that private information doesn’t leak out of the bounded context, both to avoid accidental coupling between contexts, and for security reasons. In order to do this, the output gate will often deliberately “lose” information (such as a credit card number) in the process of converting domain objects to DTOs.

A shared communication format always induces some coupling – the DTOs form a kind of contract between bounded contexts. Therefore two contexts will need to agree on a common data format in order for communication to be successful.

So how should the DTOs be defined? There are three common approaches:

- We can use a domain type as a DTO directly.

- We can convert a domain type into a DTO type that is specifically designed to be serialization-friendly, but still preserves the structure of the domain object.

- We can convert a domain type into a structureless type such as a set of key-value pairs.

The choice of which one to use depends on a couple of factors.

- In general, we want to reduce coupling between different subsystems as much as possible, so that they can evolve independently. That also means that we want to eliminate any dependencies on a particular programming language.

- Also, because the DTOs form a contract, the on-the-wire format should only be changed carefully, if at all. This means that you should always have complete control of the serialization output, and you should not just allow a library to do things auto-magically!

If we review the three approaches using these factors, here’s what we find:

The first approach (using a domain type itself as the DTO) is the easiest, but also the most problematic:

- We have created a tight coupling between the producer and the consumer of the DTO, as both of them must have intimate knowledge of the domain.

- Types developed to model a domain tend to be complex, with special types to represent choices and constraints. These are not well suited for a typical serializer to work with, and so we must use a serializer that understands F# types such as FSharpLu.Json, Chiron or FsPickler. That in turn constrains the producer and consumer to use the same serialization library.

- We probably have to mix concerns: annotating or adjusting our domain type to make the serialization process work (the approach taken by ASP.NET and some ORMs). Even then, we probably don’t have that much control of the on-the-wire format.

Overall then, this approach is not recommended, with the possible exception of when the producer and consumer of the DTO are the same (e.g. reading/writing state to a private data store, or working within a framework such as the amazing MBrace).

The second approach (creating a special DTO type to convert to) is the most straightforward to implement, if a bit tedious. This is the approach that we will focus on for most of this post.

The advantage of the last approach (creating a list of key-value pairs) is that there is no “contract” implicit in the DTO structure – a key-value map can contain anything – and so it promotes highly decoupled interactions. The downside is that there is no contract at all! That means that it is hard to know when there is a mismatch in expectations between producer and consumer. Sometimes a little bit of coupling can be useful.

The serialization process is just another component that can be added to a workflow pipeline: the deserialization step is added at the front of the workflow, and the serialization step at the end of the workflow.

For example, say that we have a pure workflow that looks like this (we’ll ignore error handling and other effects for now):

type WorkflowInput = ...

type WorkflowOutput = ...

type Workflow = WorkflowInput -> WorkflowOutput

Then the function signatures for the deserialization step might look this:

/// an alias for JSON strings

type JsonString = string

/// the DTO type corresponding to WorkflowInput

type InputDto = ...

/// deserialize a string to a DTO

type DeserializeInputDto = JsonString -> InputDto

/// convert a DTO to a domain object

type InputDtoToDomain = InputDto -> WorkflowInput

and the serialization step might look like this:

/// The DTO type corresponding to WorkflowOutput

type OutputDto = ...

/// convert a domain object to a DTO

type OutputDtoFromDomain = WorkflowOutput -> OutputDto

/// serialize a DTO to a string

type SerializeOutputDto = OutputDto -> JsonString

It’s clear that all these functions can be chained together in a pipeline, like this:

let workflowWithSerialization jsonString =

jsonString // input from infrastructure

|> deserializeInputDto // JSON to DTO

|> inputDtoToDomain // DTO to domain object

|> workflow // the core workflow within the domain

|> outputDtoFromDomain // Domain object to DTO

|> serializeOutputDto // DTO to JSON

// final output is another JsonString

And then this workflowWithSerialization function would be the one that is exposed to the infrastructure. The inputs and outputs are just JsonStrings or similar, so that the infrastructure is isolated from the domain.

Of course, it’s not quite that simple in practice! We need to handle errors, async, and so on. But this demonstrates the basic concepts.

To demonstrate the practice of serializing and deserializing a domain object to and from JSON, let’s build a small example, using the approach of having a distinct DTO object that is separate from the domain object. Say that we want to serialize a domain type Person defined like this:

module Domain = // our domain-driven types

/// constrained to be not null and at most 50 chars

type String50 = private String50 of string

module String50 = // functions for String50

let create str = ... // constructor

let value str50 = ... // value extractor

/// constrained to be bigger than 1/1/1900 and less than today's date

type Birthdate = private Birthdate of DateTime

module Birthdate = // functions for Birthdate

let create aDateTime = ... // constructor

let value birthdate = ... // value extractor

/// Domain type

type Person = {

First: String50

Last: String50

Birthdate : Birthdate

}

The String50 and Birthdate types have constraints added to them. I won’t go into details on how to do that in this post, but you can see more detailed examples here.

To start off, we create a corresponding DTO type Dto.Person (a Person type in the Dto module). In order to make serialization easy, we must ensure that

all DTO types must be simple structures containing only primitive types or other DTOs, like this:

/// A module to group all the DTO-related

/// types and functions.

module Dto =

type Person = {

First: string

Last: string

Birthdate : DateTime

}

Next, we need “toDomain” and “fromDomain” functions. These functions are associated with the DTO type, not the domain type, because the domain should not know anything about DTOs, so let’s also put them in the Dto module in a submodule called Person.

module Dto =

module Person =

/// create a DTO from a domain object

let fromDomain (person:Domain.Person) :Dto.Person =

...

/// create a domain object from a DTO

let toDomain (dto:Dto.Person) :Result<Domain.Person,string> =

...

This pattern of having a pair of fromDomain and toDomain functions is something we’ll use consistently.

Let’s start with the fromDomain function that converts a domain type into a DTO.

This function always succeeds (Result is not needed) because complex, constrained values in the domain can always be converted to primitive, unconstrained values without errors.

let fromDomain (person:Domain.Person) :Dto.Person =

// get the primitive values from the domain object

let first = person.First |> String50.value

let last = person.Last |> String50.value

let birthdate = person.Birthdate |> Birthdate.value

// combine the components to create the DTO

{First = first; Last = last; Birthdate = birthdate}

Going in the other direction, the toDomain function converts a DTO into a domain type, and because the various validations and constraints might fail, toDomain returns a Result<Person,string> rather than a plain Person.

let toDomain (dto:Dto.Person) :Result<Domain.Person,string> =

result {

// get each (validated) simple type from the DTO as a success or failure

let! first = dto.First |> String50.create "First"

let! last = dto.Last |> String50.create "Last"

let! birthdate = dto.Birthdate |> Birthdate.create

// combine the components to create the domain object

return {

First = first

Last = last

Birthdate = birthdate

}

}

We’re using a result computation expression to handle the error flow, because the simple types such as String50 and Birthdate return Result from their create methods.

For example, we might implement String50.create using the code below.

module String50 =

let create fieldName str : Result<String50,string> =

if String.IsNullOrEmpty(str) then

Error (fieldName + " must be non-empty")

elif str.Length > 50 then

Error (fieldName + " must be less that 50 chars")

else

Ok (String50 str)

Notice that we include the field name as a parameter, so that we get helpful error messages. Again, see here for other examples of constrained types.

The result computation expression is very simple. Here’s the definition:

type ResultBuilder() =

member this.Return x = Ok x

member this.Zero() = Ok ()

member this.Bind(xResult,f) = Result.bind f xResult

let result = ResultBuilder()

You can read more about using Result for error handling here.

Serializing JSON or XML is not something we want to code ourselves – we will probably prefer to use a third-party library. However, the API of the library might not be functional friendly, so we may want to wrap the serialization and deserialization routines to make them suitable for use in a pipeline, and to convert any exceptions into Results. Here’s how to wrap part of the standard .NET JSON serialization library (Newtonsoft.Json), for example:

module Json =

open Newtonsoft.Json

let serialize obj =

JsonConvert.SerializeObject obj

let deserialize<'a> str =

try

JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<'a> str

|> Result.Ok

with

// catch all exceptions and convert to Result

| ex -> Result.Error ex

We’re creating our own module Json to put the adapted versions in, so that we can call the serialization functions as Json.serialize and Json.deserialize.

With the DTO-to-domain converter and the serialization functions in place, we can take a domain type – the Person record – all the way to a JSON string:

/// Serialize a Person into a JSON string

let jsonFromDomain (person:Domain.Person) =

person

|> Dto.Person.fromDomain

|> Json.serialize

If we test it, we get the JSON string that we expect:

// input to test with

let person : Domain.Person = {

First = String50 "Alex"

Last = String50 "Adams"

Birthdate = Birthdate (DateTime(1980,1,1))

}

// use the serialization pipeline

jsonFromDomain person

// The output is

// "{"First":"Alex","Last":"Adams","Birthdate":"1980-01-01T00:00:00"}"

Composing the serialization pipeline is straightforward, because all stages are Result-free, but composing the deserialization pipeline is trickier, because both the Json.deserialize and the PersonDto.fromDomain can return Results. The solution is to use Result.mapError to convert the potential failures to a common choice type, and then use a result expression to hide the errors:

/// Define a type to represent possible errors

type DtoError =

| ValidationError of string

| DeserializationException of exn

/// Deserialize a JSON string into a Person

let jsonToDomain jsonString :Result<Domain.Person, DtoError> =

result {

let! deserializedValue =

jsonString

|> Json.deserialize

|> Result.mapError DeserializationException

let! domainValue =

deserializedValue

|> Dto.Person.toDomain

|> Result.mapError ValidationError

return domainValue

}

Let’s test it with an input that has no errors:

// JSON string to test with

let jsonPerson = """{

"First": "Alex",

"Last": "Adams",

"Birthdate": "1980-01-01T00:00:00"

}"""

// call the deserialization pipeline

jsonToDomain jsonPerson |> printfn "%A"

// The output is:

// Ok {First = String50 "Alex";

// Last = String50 "Adams";

// Birthdate = Birthdate 01/01/1980 00:00:00;}

We can see that the overall result is Ok and the Person domain object has been successfully created.

Let’s now tweak the JSON string to have errors – a blank name and a bad date – and run the code again:

let jsonPersonWithErrors = """{

"First": "",

"Last": "Adams",

"Birthdate": "1776-01-01T00:00:00"

}"""

// call the deserialization pipeline

jsonToDomain jsonPersonWithErrors |> printfn "%A"

// The output is:

// Error (ValidationError [

// "First must be non-empty"

// ])

You can see that we do indeed get the Error case of Result, and one of the validation error messages. In a real application, you could log this, and perhaps return the error to the caller.

A major problem with this particular implementation is that we only return the first error. To return all the errors, we want to combine the results “in parallel” as it were, and concatenate all the errors. This is the “applicative” approach to validation. I won’t go into details here, but I have a series of posts discussing that and more.

Another approach to error handling during deserialization is not to do it at all, and instead just let the deserialization code throw exceptions. Which approach you choose depends on whether you want to handle deserialization errors as an expected situation or as a “panic” that crashes the entire pipeline. And that in turn depends on how public your API is, how much you trust the callers, and how much information you want to provide the callers about these kinds of errors.

The code above uses the Newtonsoft.Json serializer. You can use other serializers, but you may need to add attributes to the PersonDto type. For example, to serialize a record type using the DataContractSerializer (for XML) or the old DataContractJsonSerializer (for JSON), you must decorate your DTO type with DataContractAttribute and DataMemberAttribute:

module Dto =

[<DataContract>]

type Person = {

[<field: DataMember>]

First: string

[<field: DataMember>]

Last: string

[<field: DataMember>]

Birthdate : DateTime

}

This shows one of the other advantages of keeping the DTO type separate from the domain type – the domain type is not contaminated with complex attributes like this. As always, it’s good to separate the domain concerns from the infrastructure concerns.

Another useful attribute to know about with serializers is the CLIMutableAttribute, which emits a (hidden) parameterless constructor, often needed by serializers that use reflection.

Finally, if you know that you are only going to be working with other F# components, you can use a F#-specific serializer such as FSharpLu.Json, FsPickler or Chiron, although to repeat what I said before, you are now introducing a coupling between the bounded contexts, in that they all must use the same library.

Over time, as the design evolves, the domain types may need to change, with fields added or removed, or renamed. This in turn may affect the DTO types too. I said earlier that the DTO types act as a contract, and that it is important not to break this contract. This means that you may have to support multiple versions of a DTO type over time. There are many ways to do this, which I’m not going to go into here, but I can recommend Greg Young’s book, Versioning in an Event Sourced System, for a good discussion of the various approaches available. Also, some serialization libraries, such as Protobuf, support backward compatibility with the wire-format as versions change.

In the functional approach to domain modeling, the domain types that we define are generally algebraic data types, built by composition: combining smaller types into bigger ones. The resulting top-level types can be very complex, and yet we require that the corresponding DTO types must be simple structures containing only primitive types. How then do we design a DTO, given a particular algebraic data type? In this next section, we’ll look at some guidelines.

These guidelines are not meant to be definitive. I encourage you to look at the approaches of the F# friendly JSON serializers to get some other ideas (e.g. FSharpLu.Json and Chiron).

Also, remember that there’s more to serialization than just JSON (which is I think is vastly overused). For JSON serialization, you might well be able to use the libraries already mentioned, but for other formats, you may have to roll your own, and I hope this discussion is useful in that case.

Single case unions can be represented by the underlying primitive in the DTO.

For example, if ProductCode is a domain type that wraps a string:

type ProductCode = ProductCode of string

then the corresponding DTO type is just string.

For options, we can replace the None case with null.

If the option wraps a reference type, we don’t need to do anything, as null is a valid value. For value types like int, we will need to use the nullable equivalent, such as Nullable<int>.

Domain types defined as records can stay as records in the DTO, as long as the type of each field is converted to the serialization-friendly equivalent (a primitive or another DTO).

Here’s an example demonstrating single-case unions, optional values, and a record type:

/// Domain types

type OrderLineId = OrderLineId of int

type OrderLineQty = OrderLineQty of int

type OrderLine = {

OrderLineId : OrderLineId

ProductCode : ProductCode

Quantity : OrderLineQty option

Description : string option

}

/// Corresponding DTO type

type OrderLineDto = {

OrderLineId : int

ProductCode : string

Quantity : Nullable<int>

Description : string

}

Lists, sequences, and sets should generally be converted to arrays, which are supported in every serialization format.

/// Domain type

type Order = {

...

Lines : OrderLine list

}

/// Corresponding DTO type

type OrderDto = {

...

Lines : OrderLineDto[]

}

For, maps and other complex collections, the approach you take depends on the serialization format. When using JSON, you should be able to serialize directly from a map to a JSON object, since JSON objects are just key-value collections.

For other formats you may need to create a special representation. For example, a map might be represented in a DTO as an array of records, where each record is a key-value pair:

/// Domain type

type Price = Price of decimal

type PriceLookup = Map<ProductCode,Price>

/// DTO type to represent a map

type PriceLookupPair = {

Key : string

Value : decimal

}

type PriceLookupDto = {

KVPairs : PriceLookupPair []

}

Alternatively a map can be represented as two parallel arrays that can be zipped together on deserialization.

/// Alternative DTO type to represent a map

type PriceLookupDto = {

Keys : string []

Values : decimal []

}

In many cases, you have unions where every case is a just a name with no extra data. These can be represented by .NET enums, which in turn are generally represented by integers when serialized.

/// Domain type

type Color =

| Red

| Green

| Blue

/// Corresponding DTO type

type ColorDto =

| Red = 1

| Green = 2

| Blue = 3

Note that when deserializing, you must handle the case where the .NET enum value is not one of the enumerated ones.

let toDomain dto : Result<Color,string> =

match dto with

| ColorDto.Red -> Ok Color.Red

| ColorDto.Green -> Ok Color.Green

| ColorDto.Blue -> Ok Color.Blue

| _ -> Error (sprintf "Color %O is not one of Red,Green,Blue" dto)

Alternatively, you can serialize an enum-style union as a string, using the name of the case as the value. This is more sensitive to renaming issues though.

Tuples should not really be exposed in the public API of the domain, but if you do use them, they will probably need to be represented by a specially defined record, since tuples are not supported in most serialization formats. In the example below, the domain type Card is a tuple, but the corresponding CardDto type is a record.

/// Domain types

type Suit = Heart | Spade | Diamond | Club

type Rank = Ace | Two | Queen | King // incomplete for clarity

type Card = Suit * Rank // <---- a tuple

/// Corresponding DTO types

type SuitDto = Heart = 1 | Spade = 2 | Diamond = 3 | Club = 4

type RankDto = Ace = 1 | Two = 2 | Queen = 12 | King = 13

type CardDto = {

Suit : SuitDto

Rank : RankDto

}

Choice types (discriminated unions) can be represented as a record with a “tag” that represents which choice is used, and then a field for each possible case, containing the data associated with that case. When a specific case is converted in the DTO, the field for that case will have data, and all the other fields, for the other cases, will be null (or for lists, empty).

Here’s an example of a domain type (Example) with four choices that demonstrate the different kinds of data that need to be handled:

- An empty case, tagged as

A. - An integer, tagged as

B. - A list of strings, tagged as

C. - A name (using a separate

Nametype), tagged asD.

/// Domain types

type Name = {

First : String50

Last : String50

}

type Example =

| A

| B of int

| C of string list

| D of Name

And here’s how the corresponding DTO type would look, with the type of each case being replaced with a serializable version: int to Nullable<int>, string list to string[] and Name to NameDto.

/// Corresponding DTO types

type NameDto = {

First : string

Last : string

}

type ExampleDto = {

Tag : string // one of "A","B", "C", "D"

// no data for A case

BData : Nullable<int> // data for B case

CData : string[] // data for C case

DData : NameDto // data for D case

}

Serialization is straightforward – you just need to convert the data for the selected case to a DTO-friendly value, and set the data for all the other cases to null:

let nameDtoFromDomain (name:Name) :NameDto =

let first = name.First |> String50.value

let last = name.Last |> String50.value

{First=first; Last=last}

let fromDomain (domainObj:Example) :ExampleDto =

let nullBData = Nullable()

let nullCData = null

let nullDData = Unchecked.defaultof<NameDto>

match domainObj with

| A ->

{Tag="A"; BData=nullBData; CData=nullCData; DData=nullDData}

| B i ->

let bdata = Nullable i

{Tag="B"; BData=bdata; CData=nullCData; DData=nullDData}

| C strList ->

let cdata = strList |> List.toArray

{Tag="C"; BData=nullBData; CData=cdata; DData=nullDData}

| D name ->

let ddata = name |> nameDtoFromDomain

{Tag="D"; BData=nullBData; CData=nullCData; DData=ddata}

Here’s what’s going on in this code:

- We set up the null values for each field at the top of the function, and then assign them to the fields that are not relevant to the case being matched.

- In the “B” case,

Nullable<_>types cannot be assignednulldirectly. We must use theNullable()function instead. - In the “C” case, an

Arraycan be assignednull, because it is a .NET class. - In the “D” case, an F# record such as

NameDtocannot be assigned null either, so we are using the “backdoor” functionUnchecked.defaultOf<_>to create a null value for it. This should never be used in normal code, but only when you need to create nulls for interop or serialization.

When deserializing a choice type with a tag like this, we match on the “tag” field, and then handle each case separately. And before we attempt the deserialization, we must always check that the data associated with the tag is not null:

let nameDtoToDomain (nameDto:NameDto) :Result<Name,string> =

result {

let! first = nameDto.First |> String50.create

let! last = nameDto.Last |> String50.create

return {First=first; Last=last}

}

let toDomain dto : Result<Example,string> =

match dto.Tag with

| "A" ->

Ok A

| "B" ->

if dto.BData.HasValue then

dto.BData.Value |> B |> Ok

else

Error "B data not expected to be null"

| "C" ->

match dto.CData with

| null ->

Error "C data not expected to be null"

| _ ->

dto.CData |> Array.toList |> C |> Ok

| "D" ->

match box dto.DData with

| null ->

Error "D data not expected to be null"

| _ ->

dto.DData

|> nameDtoToDomain // returns Result...

|> Result.map D // ...so must use "map"

| _ ->

// all other cases

let msg = sprintf "Tag '%s' not recognized" dto.Tag

Error msg

In the “B” and “C” cases, the conversion from the primitive value to the domain values is error free (after ensuring that the data is not null). In the “D” case, the conversion from NameDto to Name might fail, and so it returns a Result that we must map over (using Result.map) with the D case constructor.

An alternative serialization approach for compound types (records and discriminated unions) is to serialize everything as a key-value map. In other words, all DTOs will be implemented in the same way – as the .NET type IDictionary<string,obj>. This approach is particularly applicable for working with the JSON format, where it aligns well with the JSON object model.

Let’s look at some code. Using this approach, we would serialize a Name record like this:

let nameDtoFromDomain (name:Name) :IDictionary<string,obj> =

let first = name.First |> String50.value :> obj

let last = name.Last |> String50.value :> obj

[

("First",first)

("Last",last)

] |> dict

Here we’re creating a list of key/value pairs and then using the built-in function dict to build an IDictionary from them. If this dictionary is then serialized to JSON, the output looks just as if we created a separate NameDto type and serialized it.

One thing to note is that the IDictionary uses obj as the type of the value. That means that all the values in the record must be explicitly cast to obj using the upcast operator :>.

For choice types, the dictionary that is returned will have exactly one entry, but the value of the key will depend on the choice. For example, if we are serializing the Example type, the key would be one of “A,” “B,” “C” or “D.”

let fromDomain (domainObj:Example) :IDictionary<string,obj> =

match domainObj with

| A ->

[ ("A",null) ] |> dict

| B i ->

let bdata = Nullable i :> obj

[ ("B",bdata) ] |> dict

| C strList ->

let cdata = strList |> List.toArray :> obj

[ ("C",cdata) ] |> dict

| D name ->

let ddata = name |> nameDtoFromDomain :> obj

[ ("D",ddata) ] |> dict

The code above shows a similar approach to nameDtoFromDomain. For each case, we convert the data into a serializable format and then cast that to obj. In the “D” case, where the data is a Name, the serializable format is the output of nameDtoFromDomain, which is just another IDictionary.

Deserialization is a bit trickier. For each field we need to (a) look in the dictionary to see if it is there, and (b) if present, retrieve it and attempt to cast it into the correct type.

This calls out for a helper function, which we’ll call getValue:

let getValue key (dict:IDictionary<string,obj>) :Result<'a,string> =

match dict.TryGetValue key with

| (true,value) -> // key found!

try

// attempt to downcast to the type 'a and return Ok

(value :?> 'a) |> Ok

with

| :? InvalidCastException ->

// the cast failed

let typeName = typeof<'a>.Name

let msg = sprintf "Value could not be cast to %s" typeName

Error msg

| (false,_) -> // key not found

let msg = sprintf "Key '%s' not found" key

Error msg

Let’s look at how to deserialize a Name, then. We first have to get the value at the “First” key (which might result in an error). If that works, we call String50.create on it to get the First field (which also might result in an error). Similarly for the “Last” key and the Last field. As always, we’ll use a result expression to make our lives easier.

let nameDtoToDomain (nameDto:IDictionary<string,obj>) :Result<Name,string> =

result {

let! firstStr = nameDto |> getValue "First"

let! first = firstStr |> String50.create

let! lastStr = nameDto |> getValue "Last"

let! last = lastStr |> String50.create

return {First=first; Last=last}

}

To deserialize a choice type such as Example, we need to test whether a key is present for each case. If there is, we can attempt to retrieve it and convert it into a domain object. Again, there is lot of potential for errors, so for each case, we’ll use a result expression.

let toDomain (dto:IDictionary<string,obj>) : Result<Example,string> =

if dto.ContainsKey "A" then

Ok A // no extra data needed

elif dto.ContainsKey "B" then

result {

let! bData = dto |> getValue "B" // might fail

return B bData

}

elif dto.ContainsKey "C" then

result {

let! cData = dto |> getValue "C" // might fail

return cData |> Array.toList |> C

}

elif dto.ContainsKey "D" then

result {

let! dData = dto |> getValue "D" // might fail

let! name = dData |> nameDtoToDomain // might also fail

return name |> D

}

else

// all other cases

let msg = sprintf "No union case recognized"

Error msg

This is all very ugly of course, but once you understand how this works, you can make your life easier by creating a helper library along the lines of the Elm decoder library. Or you can just give up and use one of the F#-friendly libraries mentioned earlier!

In many cases, the domain type is generic. If the serialization library supports generics, then you can create DTOs using generics as well.

For example, the Result type is generic, and can be converted into a generic ResultDto like this:

type ResultDto<'OkData,'ErrorData when 'OkData : null and 'ErrorData: null> = {

IsError : bool // replaces "Tag" field

OkData : 'OkData

ErrorData : 'ErrorData

}

Note that the generic types 'OkData and 'ErrorData must be constrained to be nullable because on deserialization, they might be missing.

If the serialization library does not support generics, then you will have to create a special type for each concrete case. That might sound tedious, but you’ll probably find that in practice, very few generic types need to be serialized.

For example, here’s the Result type for a specific workflow output, converted to a DTO using concrete types rather than generic types:

type WorkflowSuccessDto = ...

type WorkflowErrorDto = ...

type WorkflowResultDto = {

IsError : bool

OkData : WorkflowSuccessDto

ErrorData : WorkflowErrorDto

}

In all the code above, we spent a lot of time assuming that the validation might fail, and working with Results. Tedious, but once written, we can be sure that we will never have unhandled errors.

But what if you are very confident that the serialized data will never contain bad data? Or what if you don’t care about error handling at all?

In that case, you can get rid of the Result logic and just throw exceptions. If errors are rare, or if you just don’t care, then you can eliminate them and make the code much simpler!

Thanks for reading, and again, check out the other F# Advent Calendar entries.

Here are the links to the F# serializers mentioned:

And if you liked this post, you’ll be glad to know that I have written a whole book on the topic of domain modeling! You can read more about it on the books page.

Happy Holidays!

Twitter

Twitter