Twenty six low-risk ways to use F# at work

So you’re all excited about functional programming, and you’ve been learning F# in your spare time, and you’re annoying your co-workers by ranting about how great it is, and you’re itching to use it for serious stuff at work…

But then you hit a brick wall.

Your workplace has a “C# only” policy and won’t let you use F#.

If you work in a typical enterprise environment, getting a new language approved will be a long drawn out process, involving persuading your teammates, the QA guys, the ops guys, your boss, your boss’s boss, and the mysterious bloke down the hall who you’ve never talked to. I would encourage you to start that process (a helpful link for your manager), but still, you’re impatient and thinking “what can I do now?”

On the other hand, perhaps you work in a flexible, easy going place, where you can do what you like.

But you’re conscientious, and don’t want to be one of those people who re-write some mission critical system in APL, and then vanish without trace, leaving your replacement some mind-bendingly cryptic code to maintain. No, you want to make sure that you are not doing anything that will affect your team’s bus factor.

So in both these scenarios, you want to use F# at work, but you can’t (or don’t want to) use it for core application code.

What can you do?

Well, don’t worry! This series of articles will suggest a number of ways you can get your hands dirty with F# in a low-risk, incremental way, without affecting any critical code.

Here’s a list of the twenty six ways so that you can go straight to any one that you find particularly interesting.

Part 1 - Using F# to explore and develop interactively

1. Use F# to explore the .NET framework interactively

2. Use F# to test your own code interactively

3. Use F# to play with webservices interactively

4. Use F# to play with UI’s interactively

Part 2 - Using F# for development and devops scripts

5. Use FAKE for build and CI scripts

6. An F# script to check that a website is responding

7. An F# script to convert an RSS feed into CSV

8. An F# script that uses WMI to check the stats of a process

9. Use F# for configuring and managing the cloud

Part 3 - Using F# for testing

10. Use F# to write unit tests with readable names

11. Use F# to run unit tests programmatically

12. Use F# to learn to write unit tests in other ways

13. Use FsCheck to write better unit tests

14. Use FsCheck to create random dummy data

15. Use F# to create mocks

16. Use F# to do automated browser testing

17. Use F# for Behaviour Driven Development

Part 4 - Using F# for database related tasks

18. Use F# to replace LINQpad

19. Use F# to unit test stored procedures

20. Use FsCheck to generate random database records

21. Use F# to do simple ETL

22. Use F# to generate SQL Agent scripts

Part 5 - Other interesting ways of using F#

23. Use F# for parsing

24. Use F# for diagramming and visualization

25. Use F# for accessing web-based data stores

26. Use F# for data science and machine learning

(BONUS) 27: Balance the generation schedule for the UK power station fleet

If you’re using Visual Studio, you’ve already got F# installed, so you’re ready to go! No need to ask anyone’s permission.

If you’re on a Mac or Linux, you will have to a bit of work, alas (instructions for Mac and Linux).

There are two ways to use F# interactively: (1) typing in the F# interactive window directly, or (2) creating a F# script file (.FSX) and then evaluating code snippets.

To use the F# interactive window in Visual Studio:

- Show the window with

Menu > View > Other Windows > F# Interactive - Type an expression, and use double semicolon (

;;) to tell the interpreter you’re finished.

For example:

let x = 1

let y = 2

x + y;;

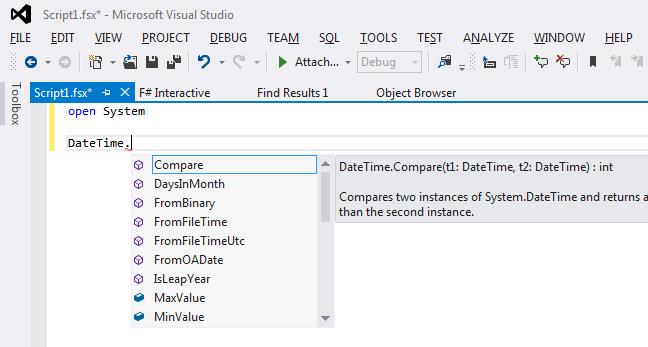

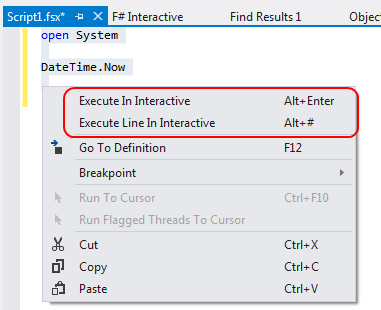

Personally, I prefer to create a script file (File > New > File then pick “F# script”) and type code there, because you get auto-complete and intellisense.

To run a bit of code, just highlight and right click, or simply do Alt+Enter.

Most of the code samples reference external libraries which are expected to be under the script directory.

You could download or compile these DLLs explicitly, but I think using NuGet from the command line is simpler.

- First, you need to install Chocolately (from chocolatey.org)

- Next install the NuGet command line using

cinst nuget.commandline - Finally, go to your script directory, and install the NuGet package from the command line.

For example,nuget install FSharp.Data -o Packages -ExcludeVersion

As you see, I prefer to exclude versions from Nuget packages when using them from scripts so that I can update later without breaking existing code.

The first area where F# is valuable is as a tool to interactively explore .NET libraries.

Before, in order to do this, you might have created unit tests and then stepped through them with a debugger to understand what is happening. But with F#, you don’t need to do that, you can run the code directly.

Let’s look at some examples.

The code for this section is available on github.

When I’m coding, I often have little questions about how the .NET library works.

For example, here are some questions that I have had recently that I answered by using F# interactively:

- Have I got a custom DateTime format string correct?

- How does XML serialization handle local DateTimes vs. UTC DateTimes?

- Is

GetEnvironmentVariablecase-sensitive?

All these questions can be found in the MSDN documentation, of course, but can also answered in seconds by running some simple F# snippets, shown below.

I want to use 24 hour clock in a custom format. I know that it’s “h”, but is it upper or lowercase “h”?

open System

DateTime.Now.ToString("yyyy-MM-dd hh:mm") // "2014-04-18 01:08"

DateTime.Now.ToString("yyyy-MM-dd HH:mm") // "2014-04-18 13:09"

How exactly, does XML serialization work with dates? Let’s find out!

// TIP: sets the current directory to be same as the script directory

System.IO.Directory.SetCurrentDirectory (__SOURCE_DIRECTORY__)

open System

[<CLIMutable>]

type DateSerTest = {Local:DateTime;Utc:DateTime}

let ser = new System.Xml.Serialization.XmlSerializer(typeof<DateSerTest>)

let testSerialization (dt:DateSerTest) =

let filename = "serialization.xml"

use fs = new IO.FileStream(filename , IO.FileMode.Create)

ser.Serialize(fs, o=dt)

fs.Close()

IO.File.ReadAllText(filename) |> printfn "%s"

let d = {

Local = DateTime.SpecifyKind(new DateTime(2014,7,4), DateTimeKind.Local)

Utc = DateTime.SpecifyKind(new DateTime(2014,7,4), DateTimeKind.Utc)

}

testSerialization d

The output is:

<DateSerTest xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xmlns:xsd="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema">

<Local>2014-07-04T00:00:00+01:00</Local>

<Utc>2014-07-04T00:00:00Z</Utc>

</DateSerTest>

So I can see it uses “Z” for UTC times.

This can be answered with a simple snippet:

Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable "ProgramFiles" =

Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable "PROGRAMFILES"

// answer => true

The answer is therefore “not case-sensitive”.

The code for this section is available on github.

You are not restricted to playing with the .NET libraries, of course. Sometimes it can be quite useful to test your own code.

To do this, just reference the DLL and then open the namespace as shown below.

// set the current directory to be same as the script directory

System.IO.Directory.SetCurrentDirectory (__SOURCE_DIRECTORY__)

// pass in the relative path to the DLL

#r @"bin\debug\myapp.dll"

// open the namespace

open MyApp

// do something

MyApp.DoSomething()

WARNING: in older versions of F#, opening a reference to your DLL will lock it so that you can’t compile it! In which case, before recompiling, be sure to reset the interactive session to release the lock. In newer versions of F#, the DLL is shadow-copied, and there is no lock.

The code for this section is available on github.

If you want to play with the WebAPI and Owin libraries, you don’t need to create an executable – you can do it through script alone!

There is a little bit of setup involved, as you will need a number of library DLLs to make this work.

So, assuming you have got the NuGet command line set up (see above), go to your script directory, and install the self hosting libraries

via nuget install Microsoft.AspNet.WebApi.OwinSelfHost -o Packages -ExcludeVersion

Once these libraries are in place, you can use the code below as a skeleton for a simple WebAPI app.

// sets the current directory to be same as the script directory

System.IO.Directory.SetCurrentDirectory (__SOURCE_DIRECTORY__)

// assumes nuget install Microsoft.AspNet.WebApi.OwinSelfHost has been run

// so that assemblies are available under the current directory

#r @"Packages\Owin\lib\net40\Owin.dll"

#r @"Packages\Microsoft.Owin\lib\net40\Microsoft.Owin.dll"

#r @"Packages\Microsoft.Owin.Host.HttpListener\lib\net40\Microsoft.Owin.Host.HttpListener.dll"

#r @"Packages\Microsoft.Owin.Hosting\lib\net40\Microsoft.Owin.Hosting.dll"

#r @"Packages\Microsoft.AspNet.WebApi.Owin\lib\net45\System.Web.Http.Owin.dll"

#r @"Packages\Microsoft.AspNet.WebApi.Core\lib\net45\System.Web.Http.dll"

#r @"Packages\Microsoft.AspNet.WebApi.Client\lib\net45\System.Net.Http.Formatting.dll"

#r @"Packages\Newtonsoft.Json\lib\net40\Newtonsoft.Json.dll"

#r "System.Net.Http.dll"

open System

open Owin

open Microsoft.Owin

open System.Web.Http

open System.Web.Http.Dispatcher

open System.Net.Http.Formatting

module OwinSelfhostSample =

/// a record to return

[<CLIMutable>]

type Greeting = { Text : string }

/// A simple Controller

type GreetingController() =

inherit ApiController()

// GET api/greeting

member this.Get() =

{Text="Hello!"}

/// Another Controller that parses URIs

type ValuesController() =

inherit ApiController()

// GET api/values

member this.Get() =

["value1";"value2"]

// GET api/values/5

member this.Get id =

sprintf "id is %i" id

// POST api/values

member this.Post ([<FromBody>]value:string) =

()

// PUT api/values/5

member this.Put(id:int, [<FromBody>]value:string) =

()

// DELETE api/values/5

member this.Delete(id:int) =

()

/// A helper class to store routes, etc.

type ApiRoute = { id : RouteParameter }

/// IMPORTANT: When running interactively, the controllers will not be found with error:

/// "No type was found that matches the controller named 'XXX'."

/// The fix is to override the ControllerResolver to use the current assembly

type ControllerResolver() =

inherit DefaultHttpControllerTypeResolver()

override this.GetControllerTypes (assembliesResolver:IAssembliesResolver) =

let t = typeof<System.Web.Http.Controllers.IHttpController>

System.Reflection.Assembly.GetExecutingAssembly().GetTypes()

|> Array.filter t.IsAssignableFrom

:> Collections.Generic.ICollection<Type>

/// A class to manage the configuration

type MyHttpConfiguration() as this =

inherit HttpConfiguration()

let configureRoutes() =

this.Routes.MapHttpRoute(

name= "DefaultApi",

routeTemplate= "api/{controller}/{id}",

defaults= { id = RouteParameter.Optional }

) |> ignore

let configureJsonSerialization() =

let jsonSettings = this.Formatters.JsonFormatter.SerializerSettings

jsonSettings.Formatting <- Newtonsoft.Json.Formatting.Indented

jsonSettings.ContractResolver <-

Newtonsoft.Json.Serialization.CamelCasePropertyNamesContractResolver()

// Here is where the controllers are resolved

let configureServices() =

this.Services.Replace(

typeof<IHttpControllerTypeResolver>,

new ControllerResolver())

do configureRoutes()

do configureJsonSerialization()

do configureServices()

/// Create a startup class using the configuration

type Startup() =

// This code configures Web API. The Startup class is specified as a type

// parameter in the WebApp.Start method.

member this.Configuration (appBuilder:IAppBuilder) =

// Configure Web API for self-host.

let config = new MyHttpConfiguration()

appBuilder.UseWebApi(config) |> ignore

// Start OWIN host

do

// Create server

let baseAddress = "http://localhost:9000/"

use app = Microsoft.Owin.Hosting.WebApp.Start<OwinSelfhostSample.Startup>(url=baseAddress)

// Create client and make some requests to the api

use client = new System.Net.Http.HttpClient()

let showResponse query =

let response = client.GetAsync(baseAddress + query).Result

Console.WriteLine(response)

Console.WriteLine(response.Content.ReadAsStringAsync().Result)

showResponse "api/greeting"

showResponse "api/values"

showResponse "api/values/42"

// for standalone scripts, pause so that you can test via your browser as well

Console.ReadLine() |> ignore

Here’s the output:

StatusCode: 200, ReasonPhrase: 'OK', Version: 1.1, Content: System.Net.Http.StreamContent, Headers:

{

Date: Fri, 18 Apr 2014 22:29:04 GMT

Server: Microsoft-HTTPAPI/2.0

Content-Length: 24

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

}

{

"text": "Hello!"

}

StatusCode: 200, ReasonPhrase: 'OK', Version: 1.1, Content: System.Net.Http.StreamContent, Headers:

{

Date: Fri, 18 Apr 2014 22:29:04 GMT

Server: Microsoft-HTTPAPI/2.0

Content-Length: 29

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

}

[

"value1",

"value2"

]

StatusCode: 200, ReasonPhrase: 'OK', Version: 1.1, Content: System.Net.Http.StreamContent, Headers:

{

Date: Fri, 18 Apr 2014 22:29:04 GMT

Server: Microsoft-HTTPAPI/2.0

Content-Length: 10

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

}

"id is 42"

This example is just to demonstrate that you can use the OWIN and WebApi libraries “out-of-the-box”.

For a more F# friendly web framework, have a look at Suave or WebSharper. There is a lot more webby stuff at fsharp.org.

The code for this section is available on github.

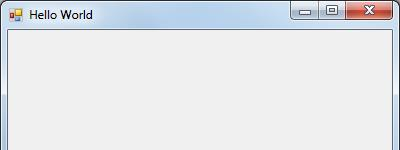

Another use for F# interactive is to play with UI’s while they are running – live!

Here’s an example of developing a WinForms screen interactively.

open System.Windows.Forms

open System.Drawing

let form = new Form(Width= 400, Height = 300, Visible = true, Text = "Hello World")

form.TopMost <- true

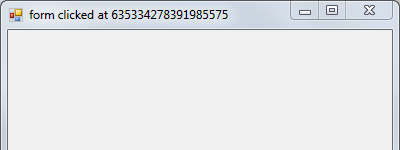

form.Click.Add (fun _ ->

form.Text <- sprintf "form clicked at %i" DateTime.Now.Ticks)

form.Show()

Here’s the window:

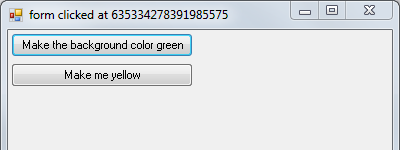

And here’s the window after clicking, with the title bar changed:

Now let’s add a FlowLayoutPanel and a button.

let panel = new FlowLayoutPanel()

form.Controls.Add(panel)

panel.Dock = DockStyle.Fill

panel.WrapContents <- false

let greenButton = new Button()

greenButton.Text <- "Make the background color green"

greenButton.Click.Add (fun _-> form.BackColor <- Color.LightGreen)

panel.Controls.Add(greenButton)

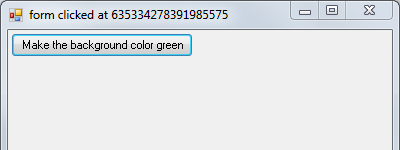

Here’s the window now:

But the button is too small – we need to set AutoSize to be true.

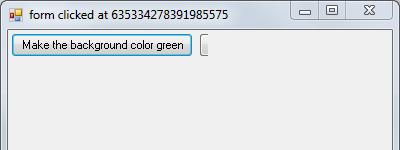

greenButton.AutoSize <- true

That’s better!

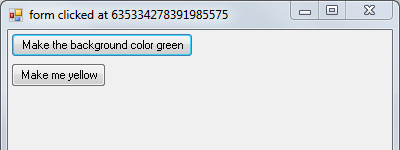

Let’s add a yellow button too:

let yellowButton = new Button()

yellowButton.Text <- "Make me yellow"

yellowButton.AutoSize <- true

yellowButton.Click.Add (fun _-> form.BackColor <- Color.Yellow)

panel.Controls.Add(yellowButton)

But the button is cut off, so let’s change the flow direction:

panel.FlowDirection <- FlowDirection.TopDown

But now the yellow button is not the same width as the green button, which we can fix with Dock:

yellowButton.Dock <- DockStyle.Fill

As you can see, it is really easy to play around with layouts interactively this way. Once you’re happy with the layout logic, you can convert the code back to C# for your real application.

This example is WinForms specific. For other UI frameworks the logic would be different, of course.

So that’s the first four suggestions. We’re not done yet! The next post will cover using F# for development and devops scripts.

Twitter

Twitter