Function associativity and composition

If we have a chain of functions in a row, how are they combined?

For example, what does this mean?

let F x y z = x y z

Does it mean apply the function y to the argument z, and then take the result and use it as an argument for x? In which case it is the same as:

let F x y z = x (y z)

Or does it mean apply the function x to the argument y, and then take the resulting function and evaluate it with the argument z? In which case it is the same as:

let F x y z = (x y) z

The answer is the latter. Function application is left associative. That is, evaluating x y z is the same as evaluating (x y) z. And evaluating w x y z is the same as evaluating ((w x) y) z. This should not be a surprise. We have already seen that this is how partial application works. If you think of x as a two parameter function, then (x y) z is the result of partial application of the first parameter, followed by passing the z argument to the intermediate function.

If you do want to do right association, you can use explicit parentheses, or you can use a pipe. The following three forms are equivalent.

let F x y z = x (y z)

let F x y z = y z |> x // using forward pipe

let F x y z = x <| y z // using backward pipe

As an exercise, work out the signatures for these functions without actually evaluating them!

We’ve mentioned function composition a number of times in passing now, but what does it actually mean? It can seem quite intimidating at first, but it is actually quite simple.

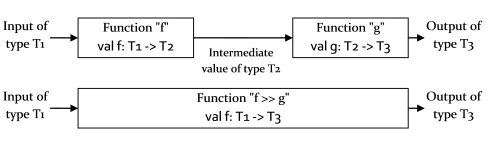

Say that you have a function “f” that maps from type “T1” to type “T2”, and say that you also have a function “g” that maps from type “T2” to type “T3”. Then you can connect the output of “f” to the input of “g”, creating a new function that maps from type “T1” to type “T3”.

Here’s an example

let f (x:int) = float x * 3.0 // f is int->float

let g (x:float) = x > 4.0 // g is float->bool

We can create a new function h that takes the output of “f” and uses it as the input for “g”.

let h (x:int) =

let y = f(x)

g(y) // return output of g

A much more compact way is this:

let h (x:int) = g ( f(x) ) // h is int->bool

//test

h 1

h 2

So far, so straightforward. What is interesting is that we can define a new function called “compose” that, given functions “f” and “g”, combines them in this way without even knowing their signatures.

let compose f g x = g ( f(x) )

If you evaluate this, you will see that the compiler has correctly deduced that if “f” is a function from generic type 'a to generic type 'b, then “g” is constrained to have generic type 'b as an input. And the overall signature is:

val compose : ('a -> 'b) -> ('b -> 'c) -> 'a -> 'c

(Note that this generic composition operation is only possible because every function has one input and one output. This approach would not be possible in a non-functional language.)

As we have seen, the actual definition of compose uses the “>>” symbol.

let (>>) f g x = g ( f(x) )

Given this definition, we can now use composition to build new functions from existing ones.

let add1 x = x + 1

let times2 x = x * 2

let add1Times2 x = (>>) add1 times2 x

//test

add1Times2 3

This explicit style is quite cluttered. We can do a few things to make it easier to use and understand.

First, we can leave off the x parameter so that the composition operator returns a partial application.

let add1Times2 = (>>) add1 times2

And now we have a binary operation, so we can put the operator in the middle.

let add1Times2 = add1 >> times2

And there you have it. Using the composition operator allows code to be cleaner and more straightforward.

let add1 x = x + 1

let times2 x = x * 2

//old style

let add1Times2 x = times2(add1 x)

//new style

let add1Times2 = add1 >> times2

The composition operator (like all infix operators) has lower precedence than normal function application. This means that the functions used in composition can have arguments without needing to use parentheses.

For example, if the “add” and “times” functions have an extra parameter, this can be passed in during the composition.

let add n x = x + n

let times n x = x * n

let add1Times2 = add 1 >> times 2

let add5Times3 = add 5 >> times 3

//test

add5Times3 1

As long as the inputs and outputs match, the functions involved can use any kind of value. For example, consider the following, which performs a function twice:

let twice f = f >> f //signature is ('a -> 'a) -> ('a -> 'a)

Note that the compiler has deduced that the function f must use the same type for both input and output.

Now consider a function like “+”. As we have seen earlier, the input is an int, but the output is actually a partially applied function (int->int). The output of “+” can thus be used as the input of “twice”. So we can write something like:

let add1 = (+) 1 // signature is (int -> int)

let add1Twice = twice add1 // signature is also (int -> int)

//test

add1Twice 9

On the other hand, we can’t write something like:

let addThenMultiply = (+) >> (*)

because the input to “*” must be an int value, not an int->int function (which is what the output of addition is).

But if we tweak it so that the first function has an output of just int instead, then it does work:

let add1ThenMultiply = (+) 1 >> (*)

// (+) 1 has signature (int -> int) and output is an 'int'

//test

add1ThenMultiply 2 7

Composition can also be done backwards using the “<<” operator, if needed.

let times2Add1 = add 1 << times 2

times2Add1 3

Reverse composition is mainly used to make code more English-like. For example, here is a simple example:

let myList = []

myList |> List.isEmpty |> not // straight pipeline

myList |> (not << List.isEmpty) // using reverse composition

At this point, you might be wondering what the difference is between the composition operator and the pipeline operator, as they can seem quite similar.

First let’s look again at the definition of the pipeline operator:

let (|>) x f = f x

All it does is allow you to put the function argument in front of the function rather than after. That’s all. If the function has multiple parameters, then the input would be the final parameter. Here’s the example used earlier.

let doSomething x y z = x+y+z

doSomething 1 2 3 // all parameters after function

3 |> doSomething 1 2 // last parameter piped in

Composition is not the same thing and cannot be a substitute for a pipe. In the following case the number 3 is not even a function, so its “output” cannot be fed into doSomething:

3 >> doSomething 1 2 // not allowed

// f >> g is the same as g(f(x)) so rewriting it we have:

doSomething 1 2 ( 3(x) ) // implies 3 should be a function!

// error FS0001: This expression was expected to have type 'a->'b

// but here has type int

The compiler is complaining that “3” should be some sort of function 'a->'b.

Compare this with the definition of composition, which takes 3 arguments, where the first two must be functions.

let (>>) f g x = g ( f(x) )

let add n x = x + n

let times n x = x * n

let add1Times2 = add 1 >> times 2

Trying to use a pipe instead doesn’t work. In the following example, “add 1” is a (partial) function of type int->int, and cannot be used as the second parameter of “times 2”.

let add1Times2 = add 1 |> times 2 // not allowed

// x |> f is the same as f(x) so rewriting it we have:

let add1Times2 = times 2 (add 1) // add1 should be an int

// error FS0001: Type mismatch. 'int -> int' does not match 'int'

The compiler is complaining that “times 2” should take an int->int parameter, that is, be of type (int->int)->'a.

Twitter

Twitter