Choosing properties in practice, part 2

In the previous post, we tested some list functions using various properties. Let’s keep going and test some more code in the same way. For this post, our challenge will be to test roman numeral conversion logic.

- “Two heads are better than one” applied to two different implementations

- “There and back again” applied to encoding and decoding roman numerals

- “Solving a smaller problem” applied to decoding roman numerals

- “Some things never change”. Invariants applied to roman numeral encoding

- “Different paths, same destination” applied to transforming roman numerals

In my post “Commentary on ‘Roman Numerals Kata with Commentary’" I came up with two completely different algorithms for generating Roman Numerals.

The first algorithm was based on understanding that Roman numerals were based on tallying

In other words, replace five strokes with a “V”, replace two Vs with an X and so on, leading to this simple implementation:

module TallyImpl =

let arabicToRoman arabic =

(String.replicate arabic "I")

.Replace("IIIII","V")

.Replace("VV","X")

.Replace("XXXXX","L")

.Replace("LL","C")

.Replace("CCCCC","D")

.Replace("DD","M")

// optional substitutions

.Replace("IIII","IV")

.Replace("VIV","IX")

.Replace("XXXX","XL")

.Replace("LXL","XC")

.Replace("CCCC","CD")

.Replace("DCD","CM")

If we test this interactively, we get what seems like correct behavior.

TallyImpl.arabicToRoman 1 //=> "I"

TallyImpl.arabicToRoman 9 //=> "IX"

TallyImpl.arabicToRoman 24 //=> "XXIV"

TallyImpl.arabicToRoman 999 //=> "CMXCIX"

TallyImpl.arabicToRoman 1493 //=> "MCDXCIII"

Another way to think about Roman numerals is to imagine an abacus. Each wire has four “unit” beads and one “five” bead.

This leads to the so-called “bi-quinary” approach:

module BiQuinaryImpl =

let biQuinaryDigits place (unit,five,ten) arabic =

let digit = arabic % (10*place) / place

match digit with

| 0 -> ""

| 1 -> unit

| 2 -> unit + unit

| 3 -> unit + unit + unit

| 4 -> unit + five // changed to be one less than five

| 5 -> five

| 6 -> five + unit

| 7 -> five + unit + unit

| 8 -> five + unit + unit + unit

| 9 -> unit + ten // changed to be one less than ten

| _ -> failwith "Expected 0-9 only"

let arabicToRoman arabic =

let units = biQuinaryDigits 1 ("I","V","X") arabic

let tens = biQuinaryDigits 10 ("X","L","C") arabic

let hundreds = biQuinaryDigits 100 ("C","D","M") arabic

let thousands = biQuinaryDigits 1000 ("M","?","?") arabic

thousands + hundreds + tens + units

Again, if we test interactively, the results look good.

BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman 1 //=> "I"

BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman 9 //=> "IX"

BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman 24 //=> "XXIV"

BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman 999 //=> "CMXCIX"

BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman 1493 //=> "MCDXCIII"

But how can we be sure these implementations are correct for all numbers, not just the ones we tested?

One way to gain confidence is to use the test oracle approach – compare them to each other. It’s a great way to cross-check two different implementations when you’re not sure that either implementation is right!

let biquinary_eq_tally number =

let tallyResult = TallyImpl.arabicToRoman number

let biquinaryResult = BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman number

tallyResult = biquinaryResult

But if we try running this code, we get a ArgumentException: The input must be non-negative due to the String.replicate call.

Check.Quick biquinary_eq_tally

// ArgumentException: The input must be non-negative.

So we need to only include inputs that are positive. We also need to exclude numbers that are greater than 4000, say, since the algorithms break down there too.

How can we implement this filter?

We saw in an earlier post that we could use preconditions. But for this example, we’ll try something different and change the generator.

First we’ll define a integer generator (an “arbitrary”) called arabicNumber which is filtered as we want (if you recall, an “arbitrary” is a combination of a generator algorithm and a shrinker algorithm, as described earlier). We’ll only include numbers from 1 to 4000.

let arabicNumber =

Arb.Default.Int32()

|> Arb.filter (fun i -> i > 0 && i <= 4000)

Next, we create a new property which is constrained to only use the arabicNumber generator by using the Prop.forAll helper.

let biquinary_eq_tally_withinRange =

Prop.forAll arabicNumber biquinary_eq_tally

Now finally, we can do the cross-check test again:

Check.Quick biquinary_eq_tally_withinRange

// Ok, passed 100 tests.

And we’re good! Both algorithms work correctly, it seems.

How many roman numbers do we have in total? 4000 we said. So why not test them all?

Let’s run all 4000 numbers through our property, and filter out the ones that succeed, leaving only the ones that fail, like this:

[1..4000] |> List.choose (fun i ->

if biquinary_eq_tally i then None else Some i

)

// output => [4000]

We would expect there to be no numbers that failed, and the output list to be empty, but actually there is one number in the list: 4000!

If we check the two conversions for 4000 we can see how they differ. The biquinary implementation didn’t know how to handle it. The tally implementation is less brittle and would work for higher numbers without breaking.

TallyImpl.arabicToRoman 4000 //=> "MMMM"

BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman 4000 //=> "M?"

Is this something we care about? Maybe not. We might want to restrict the inputs to the implementations to be less than 4000 though. For example, we could alter the tally implementation to return Some or None like this:

let arabicToRoman arabic =

if (arabic <= 0 || arabic >= 4000) then

None

else

(String.replicate arabic "I")

.Replace("IIIII","V")

.Replace("VV","X")

// etc

|> Some

Tip: If your domain is small enough, why not check all the values in it?

For an example from a different domain, see the post “There are Only Four Billion Floats – So Test Them All!". It uses a “test oracle” approach to check an implementation against all four billion floats.

This little hiccup is a reminder then, that property-based checking is not a golden hammer. It generates random data, but it is not necessarily the best way of probing a domain at the boundaries. If you do have well known boundaries, it’s best to create some specific tests for them, either using a custom generator for your PBT tool, or by simply doing some explicit example-based tests for the edge cases, like this:

for i in [3999..4001] do

if not (biquinary_eq_tally i) then

failwithf "test failed for %i" i

Another approach to testing these roman numeral implementations would be to create an inverse function, such that applying the original and then applying the inverse gets you back to the original state.

If we think of the roman numeral conversion as an “encoding”, then we will need to write a corresponding “decoder”. Here’s a very simple one using the same “tally” based approach that we used originally:

let romanToArabic (str:string) =

str

.Replace("CM","DCD")

.Replace("CD","CCCC")

.Replace("XC","LXL")

.Replace("XL","XXXX")

.Replace("IX","VIV")

.Replace("IV","IIII")

.Replace("M","DD")

.Replace("D","CCCCC")

.Replace("C","LL")

.Replace("L","XXXXX")

.Replace("X","VV")

.Replace("V","IIIII")

.Length

and here’s some ad-hoc tests

TallyDecode.romanToArabic "I" //=> 1

TallyDecode.romanToArabic "IX" //=> 9

TallyDecode.romanToArabic "XXIV" //=> 24

TallyDecode.romanToArabic "CMXCIX" //=> 999

TallyDecode.romanToArabic "MCDXCIII"//=> 1493

With the inverse function now available, we can write a property based test. Note that we’re using the same arabicNumber generator to limit the inputs:

/// encoding then decoding should return

/// the original number

let encodeThenDecode_eq_original =

// define an inner property

let innerProp arabic1 =

let arabic2 =

arabic1

|> TallyImpl.arabicToRoman // encode

|> TallyDecode.romanToArabic // decode

// should be same

arabic1 = arabic2

Prop.forAll arabicNumber innerProp

And if we run the test, it passes.

Check.Quick encodeThenDecode_eq_original

// Ok, passed 100 tests.

We can also check the biquinary encoding against the tally-based decoding

/// encoding then decoding should return

/// the original number

let encodeThenDecode_eq_original2 =

// define an inner property

let innerProp arabic1 =

let arabic2 =

arabic1

|> BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman // encode

|> TallyDecode.romanToArabic // decode

// should be same

arabic1 = arabic2

Prop.forAll arabicNumber innerProp

And if we run the test, it passes again.

Check.Quick encodeThenDecode_eq_original2

// Ok, passed 100 tests.

Yet another way of checking that the implementation is correct is to break it down into smaller components and check that the smaller components are correct.

For example, if the we break the Arabic number into 1000s, 100s, 10s, and units, and then encode them separately, the concatenation of these components should be the same as the original Arabic number encoded directly.

let recursive_prop =

// define an inner property

let innerProp arabic =

let thousands =

(arabic / 1000 % 10) * 1000

|> BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman

let hundreds =

(arabic / 100 % 10) * 100

|> BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman

let tens =

(arabic / 10 % 10) * 10

|> BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman

let units =

arabic % 10

|> BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman

let direct =

arabic

|> BiQuinaryImpl.arabicToRoman

// should be same

direct = thousands+hundreds+tens+units

Prop.forAll arabicNumber innerProp

And, it works great!

Check.Quick recursive_prop

// Ok, passed 100 tests.

As we mentioned last time, invariants are often a great way to beat the EDFH. On their own, they can not prove that an implementation is correct, but in conjunction with other properties they are a very powerful tool.

So, what invariants are there for a roman numeral encoding?

Well, there are no obvious things which are preserved between the input and the output of the encoding, such as the length of a string, or the contents of a collection.

However, there are some properties which are preserved when a roman numeral is created from another roman numeral using arithmetic. For example, there are never more than three “I"s, or one “V”, etc. We can test these invariants easily.

First, we need a function to count the number of occurrences of a pattern:

let matchesFor pattern input =

System.Text.RegularExpressions.Regex.Matches(input,pattern).Count

(*

"MMMCXCVIII" |> matchesFor "I" //=> 3

"MMMCXCVIII" |> matchesFor "XC" //=> 1

"MMMCXCVIII" |> matchesFor "C" //=> 2

"MMMCXCVIII" |> matchesFor "M" //=> 3

*)

and then we can define our property using those invariants:

let invariant_prop =

let maxMatchesFor pattern n input =

(matchesFor pattern input) <= n

// define an inner property

let innerProp arabic =

let roman = arabic |> TallyImpl.arabicToRoman

(roman |> maxMatchesFor "I" 3)

&& (roman |> maxMatchesFor "V" 1)

&& (roman |> maxMatchesFor "X" 4)

&& (roman |> maxMatchesFor "L" 1)

&& (roman |> maxMatchesFor "C" 4)

// etc

Prop.forAll arabicNumber innerProp

And if we test it, it works as expected.

Check.Quick invariant_prop

// Ok, passed 100 tests.

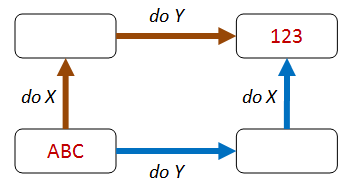

How far can we go with these patterns? We haven’t done the commutive diagram approach yet – can we apply that to the roman numeral encoding as well?

Yes, we can. It’s not really the most appropriate way to test this, but it’s a fun game to see what you can come up with!

How about this for the two paths:

- Path 1

- given a number less than 400

- encode it first

- then replace “C” with “M”, “X” with “C”, and so on, to create a new roman numeral.

- Path 2

- given the same number

- multiply it by 10 first

- then encode it

The two paths should give the same result.

/// Encoding a number less than 400 and then replacing

/// all the characters with the corresponding 10x higher one

/// should be the same as encoding the 10x number directly.

let commutative_prop1 =

// define an inner property

let innerProp arabic =

// take the part < 1000

let arabic = arabic % 1000

// encode it

let result1 =

(TallyImpl.arabicToRoman arabic)

.Replace("C","M")

.Replace("L","D")

.Replace("X","C")

.Replace("V","L")

.Replace("I","X")

// encode the 10x number

let result2 =

TallyImpl.arabicToRoman (arabic * 10)

// should be same

result1 = result2

Prop.forAll arabicNumber innerProp

And, amazingly, it works!

Check.Quick commutative_prop1

// Ok, passed 100 tests.

What about the converse:

- Path 1

- given a number less than 4000

- encode it first

- then replace “C” with “X”, “M” with “C”, and so on, to create a new roman numeral.

- Path 2

- given the same number

- divide it by 10 first

- then encode it

/// Encoding a number and then replacing all the characters with

/// the corresponding 10x lower one should be the same as

/// encoding the 10x lower number directly.

let commutative_prop2 =

// define an inner property

let innerProp arabic =

// encode it

let result1 =

(TallyImpl.arabicToRoman arabic)

.Replace("I","")

.Replace("V","")

.Replace("X","I")

.Replace("L","V")

.Replace("C","X")

.Replace("D","L")

.Replace("M","C")

// encode the 10x lower number

let result2 =

TallyImpl.arabicToRoman (arabic / 10)

// should be same

result1 = result2

Prop.forAll arabicNumber innerProp

This time, it fails, with “9” as a counter-example. Why is this?

Check.Quick commutative_prop2

// Falsifiable, after 9 tests

// 9

That can be an exercise for the reader!

I hope you get the idea now. By trying out the various approaches (oracles, inverses, invariants, commutative diagrams, etc.) we can almost always come up with useful properties for our design.

With that, we have come to the end of the various property categories. We’ll go over them one more time in a minute – but first, an interlude.

If you sometimes feel that trying to find properties is a mental challenge, you’re not alone. Would it help to pretend that it is a game?

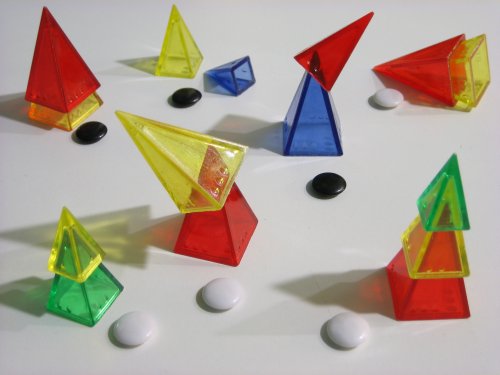

As it happens, there is a game based on finding properties.

It’s called Zendo and it involves placing sets of objects (such as plastic pyramids) on a table, such that each layout conforms to a pattern – a rule – or as we would now say, a property!.

The other players then have to guess what the rule (property) is, based on what they can see.

Here’s a picture of a Zendo game in progress:

The white stones mean the property has been satisfied, while black stones mean failure. Can you guess the rule here? I’m going to guess that it’s something like “a set must have a yellow pyramid that’s not touching the ground”.

Alright, I suppose Zendo wasn’t really inspired by property-based testing, but it is a fun game, and it has even been known to make an appearance at programming conferences.

If you want to learn more about Zendo, the rules are here.

In the next post we will keep going and use the same techniques to test a classic TDD example.

Source code used in this post is available here.

Twitter

Twitter