Working with non-monoids

In the previous posts in this series, we only dealt with things that were proper monoids.

But what if the thing you want to work with is not a monoid? What then? Well, in this post, I’ll give you some tips on converting almost anything into a monoid.

In the process, we’ll be introduced to a number of important and common functional design idioms, such as preferring lists rather than singletons, and using the option type at every opportunity.

If you recall, for a proper monoid, we need three things to be true: closure, associativity, and identity. Each requirement can present a challenge, so we’ll discuss each in turn.

We’ll start with closure.

In some cases you might want to add values together, but the type of the combined value is not the same as the type of the original values. How can you handle this?

One way is to just map from the original type to a new type that is closed. We saw this approach used with the Customer and CustomerStats example in the previous post.

In many cases, this is the easiest approach, because you don’t have to mess with the design of the original types.

On the other hand, sometimes you really don’t want to use map, but instead want to design your type from the beginning so that it meets the closure requirement.

Either way, whether you are designing a new type or redesigning an existing type, you can use similar techniques to get closure.

Obviously, we’ve seen that numeric types are closed under some basic math operations like addition and multiplication. We’ve also seen that some non-numeric types, like strings and lists, are closed under concatenation.

With this in mind, it should be obvious that any combination of these types will be closed too. We just have to define the “add” function to do the appropriate “add” on the component types.

Here’s an example:

type MyType = {count:int; items:int list}

let addMyType t1 t2 =

{count = t1.count + t2.count;

items = t1.items @ t2.items}

The addMyType function uses integer addition on the int field, and list concatenation on the list field.

As a result the MyType is closed using the function addMyType – in fact, not only is it closed, it is a monoid too. So in this case, we’re done!

This is exactly the approach we took with CustomerStats in the previous post.

So here’s my first tip:

- DESIGN TIP: To easily create a monoidal type, make sure that each field of the type is also a monoid.

Question to think about: when you do this, what is the “zero” of the new compound type?

The approach above works when creating compound types. But what about non-numeric types, which have no obvious numeric equivalent?

Here’s a very simple case. Say that you have some chars that you want to add together, like this:

'a' + 'b' -> what?

But, a char plus a char is not another char. If anything, it is a string.

'a' + 'b' -> "ab" // Closure fail!

But that is very unhelpful, as it does not meet the closure requirement.

One way to fix this is to force the chars into strings, which does work:

"a" + "b" -> "ab"

But that is a specific solution for chars – is there a more generic solution that will work for other types?

Well, think for a minute what the relationship of a string to a char is. A string can be thought of as a list or array of chars.

In other words, we could have used lists of chars instead, like this:

['a'] @ ['b'] -> ['a'; 'b'] // Lists FTW!

This meets the closure requirement as well.

What’s more, this is in fact a general solution to any problem like this, because anything can be put into a list, and lists (with concatenation) are always monoids.

So here’s my next tip:

- DESIGN TIP: To enable closure for a non-numeric type, replace single items with lists.

In some cases, you might need to convert to a list when setting up the monoid and then convert to another type when you are done.

For example, in the Char case, you would do all your manipulation on lists of chars and then only convert to a string at the end.

So let’s have a go at creating a “monoidal char” module.

module MonoidalChar =

open System

/// "monoidal char"

type MChar = MChar of Char list

/// convert a char into a "monoidal char"

let toMChar ch = MChar [ch]

/// add two monoidal chars

let addChar (MChar l1) (MChar l2) =

MChar (l1 @ l2)

// infix version

let (++) = addChar

/// convert to a string

let toString (MChar cs) =

new System.String(List.toArray cs)

You can see that MChar is a wrapper around a list of chars, rather than a single char.

Now let’s test it:

open MonoidalChar

// add two chars and convert to string

let a = 'a' |> toMChar

let b = 'b' |> toMChar

let c = a ++ b

c |> toString |> printfn "a + b = %s"

// result: "a + b = ab"

If we want to get fancy we can use map/reduce to work on a set of chars, like this:

[' '..'z'] // get a lot of chars

|> List.filter System.Char.IsPunctuation

|> List.map toMChar

|> List.reduce addChar

|> toString

|> printfn "punctuation chars are %s"

// result: "punctuation chars are !"#%&'()*,-./:;?@[\]_"

The MonoidalChar example is trivial, and could perhaps be implemented in other ways, but in general this is an extremely useful technique.

For example, here is a simple module for doing some validation. There are two options, Success and Failure, and the Failure case also has a error string associated with it.

module Validation =

type ValidationResult =

| Success

| Failure of string

let validateBadWord badWord (name:string) =

if name.Contains(badWord) then

Failure ("string contains a bad word: " + badWord)

else

Success

let validateLength maxLength name =

if String.length name > maxLength then

Failure "string is too long"

else

Success

In practice, we might perform multiple validations on a string, and we would like to return all the results at once, added together somehow.

This calls out for being a monoid! If we can add two results pairwise, then we can extend the operation to add as many results as we like!

So then the question is, how do we combine two validation results?

let result1 = Failure "string is null or empty"

let result2 = Failure "string is too long"

result1 + result2 = ????

A naive approach would be to concatenate the strings, but that wouldn’t work if we were using format strings, or resource ids with localization, etc.

No, a better way is to convert the Failure case to use a list of strings instead of a single string. That will make combining results simple.

Here’s the same code as above, with the Failure case redefined to use a list:

module MonoidalValidation =

type ValidationResult =

| Success

| Failure of string list

// helper to convert a single string into the failure case

let fail str =

Failure [str]

let validateBadWord badWord (name:string) =

if name.Contains(badWord) then

fail ("string contains a bad word: " + badWord)

else

Success

let validateLength maxLength name =

if String.length name > maxLength then

fail "string is too long"

else

Success

You can see that the individual validations call fail with a single string, but behind the scenes it is being stored as a list of strings, which can, in turn, be concatenated together.

With this in place, we can now create the add function.

The logic will be:

- If both results are

Success, then the combined result isSuccess - If one result is

Failure, then the combined result is that failure. - If both results are

Failure, then the combined result is aFailurewith both error lists concatenated.

Here’s the code:

module MonoidalValidation =

// as above

/// add two results

let add r1 r2 =

match r1,r2 with

| Success, Success -> Success

| Failure f1, Success -> Failure f1

| Success, Failure f2 -> Failure f2

| Failure f1, Failure f2 -> Failure (f1 @ f2)

Here are some tests to check the logic:

open MonoidalValidation

let test1 =

let result1 = Success

let result2 = Success

add result1 result2

|> printfn "Result is %A"

// "Result is Success"

let test2 =

let result1 = Success

let result2 = fail "string is too long"

add result1 result2

|> printfn "Result is %A"

// "Result is Failure ["string is too long"]"

let test3 =

let result1 = fail "string is null or empty"

let result2 = fail "string is too long"

add result1 result2

|> printfn "Result is %A"

// Result is Failure

// [ "string is null or empty";

// "string is too long"]

And here’s a more realistic example, where we have a list of validation functions that we want to apply:

let test4 =

let validationResults str =

[

validateLength 10

validateBadWord "monad"

validateBadWord "cobol"

]

|> List.map (fun validate -> validate str)

"cobol has native support for monads"

|> validationResults

|> List.reduce add

|> printfn "Result is %A"

The output is a Failure with three error messages.

Result is Failure

["string is too long"; "string contains a bad word: monad";

"string contains a bad word: cobol"]

One more thing is needed to finish up this monoid. We need a “zero” as well. What should it be?

By definition, it is something that when combined with another result, leaves the other result alone.

I hope you can see that by this definition, “zero” is just Success.

module MonoidalValidation =

// as above

// identity

let zero = Success

As you know, we would need to use zero if the list to reduce over is empty.

So here’s an example where we don’t apply any validation functions at all, giving us an empty list of ValidationResult.

let test5 =

let validationResults str =

[]

|> List.map (fun validate -> validate str)

"cobol has native support for monads"

|> validationResults

|> List.fold add zero

|> printfn "Result is %A"

// Result is Success

Note that we needed to change reduce to fold as well, otherwise we would get a runtime error.

Here’s one more example of the benefit of using lists. Compared with other methods of combination, list concatenation is relatively cheap, both in computation and in memory use, because the objects being pointed to don’t have to change or be reallocated.

For example, in the previous post, we defined a Text block that wrapped a string, and used string concatenation to add their contents.

type Text = Text of string

let addText (Text s1) (Text s2) =

Text (s1 + s2)

But for large strings this continual concatenation can be expensive.

Consider a different implementation, where the Text block contains a list of strings instead.

type Text = Text of string list

let addText (Text s1) (Text s2) =

Text (s1 @ s2)

Almost no change in implementation, but performance will probably be greatly improved.

You can do all your manipulation on lists of strings and you need only convert to a normal string at the very end of the processing sequence.

And if lists aren’t performant enough for you, you can easily extend this approach to use classic data structures like trees, heaps, etc. or mutable types like ResizeArray. (See the appendix on performance at the bottom of this post for some more discussion on this)

The concept of using a list of objects as a monoid is common in mathematics, where it is called a “free monoid”. In computer science, it also called

a “Kleene star” such as A*. And if you don’t allow empty lists, then you have no zero element. This variant is called a “free semigroup” or “Kleene plus” such as A+.

This “star” and “plus” notation will surely be familiar to you if you have ever used regular expressions.*

Now that we have dealt with closure, let’s take on associativity.

We saw a couple of non-associative operations in the very first post, including subtraction and division.

We can see that 5 - (3 - 2) is not equal to (5 - 3) - 2. This shows that subtraction is not associative, and

also 12 / (3 / 2) is not equal to (12 / 3) / 2, which shows that division is not associative.

There’s no single correct answer in these cases, because you might genuinely care about different answers depending on whether you work from left to right or right to left.

In fact, the F# standard libraries have two versions of fold and reduce to cater for each preference. The normal fold and reduce work left to right, like this:

//same as (12 - 3) - 2

[12;3;2] |> List.reduce (-) // => 7

//same as ((12 - 3) - 2) - 1

[12;3;2;1] |> List.reduce (-) // => 6

But there is also foldBack and reduceBack that work from right to left, like this:

//same as 12 - (3 - 2)

[12;3;2] |> List.reduceBack (-) // => 11

//same as 12 - (3 - (2 - 1))

[12;3;2;1] |> List.reduceBack (-) // => 10

In a sense, then, the associativity requirement is just a way of saying that you should get the same answer no matter whether you use fold or foldBack.

But assuming that you do want a consistent monoidal approach, the trick in many cases is to move the operation into a property of each element. Make the operation a noun, rather than a verb.

For example 3 - 2 can be thought of as 3 + (-2). Rather than “subtraction” as a verb, we have “negative 2” as a noun.

In that case, the above example becomes 5 + (-3) + (-2).

And since we are now using addition as the operator, we do have associativity, and 5 + (-3 + -2) is indeed the same as (5 + -3) + -2.

A similar approach works with division. 12 / 3 / 2 can be converted into 12 * (1/3) * (1/2), and now we are back to multiplication as the operator, which is associative.

This approach of converting the operator into a property of the element can be generalized nicely.

So here’s a tip:

- DESIGN TIP: To get associativity for an operation, try to move the operation into the object.

We can revisit an earlier example to understand how this works.

If you recall, in the first post we tried to come up with a non-associative operation for strings, and settled on subtractChars.

Here’s a simple implementation of subtractChars

let subtractChars (s1:string) (s2:string) =

let isIncluded (ch:char) = s2.IndexOf(ch) = -1

let chars = s1.ToCharArray() |> Array.filter isIncluded

System.String(chars)

// infix version

let (--) = subtractChars

With this implementation we can do some interactive tests:

"abcdef" -- "abd" // "cef"

"abcdef" -- "" // "abcdef"

And we can see for ourselves that the associativity requirement is violated:

("abc" -- "abc") -- "abc" // ""

"abc" -- ("abc" -- "abc") // "abc"

How can we make this associative?

The trick is move the “subtract-ness” from the operator into the object, just as we did with the numbers earlier.

What I mean is that we replace the plain strings with a “subtract” or “chars to remove” data structure that captures what we want to remove, like so:

let removalAction = (subtract "abd") // a data structure

And then we “apply” the data structure to the string:

let removalAction = (subtract "abd")

removalAction |> applyTo "abcdef" // "Result is cef"

Once we use this approach, we can rework the non-associative example above to look something like this:

let removalAction = (subtract "abc") + (subtract "abc") + (subtract "abc")

removalAction |> applyTo "abc" // "Result is "

Yes, it is not exactly the same as the original code, but you might find that this is actually a better fit in many situations.

The implementation is below. We define a CharsToRemove to contain a set of chars, and the other function implementations fall out from that in a straightforward way.

/// store a list of chars to remove

type CharsToRemove = CharsToRemove of Set<char>

/// construct a new CharsToRemove

let subtract (s:string) =

s.ToCharArray() |> Set.ofArray |> CharsToRemove

/// apply a CharsToRemove to a string

let applyTo (s:string) (CharsToRemove chs) =

let isIncluded ch = Set.exists ((=) ch) chs |> not

let chars = s.ToCharArray() |> Array.filter isIncluded

System.String(chars)

// combine two CharsToRemove to get a new one

let (++) (CharsToRemove c1) (CharsToRemove c2) =

CharsToRemove (Set.union c1 c2)

Let’s test!

let test1 =

let removalAction = (subtract "abd")

removalAction |> applyTo "abcdef" |> printfn "Result is %s"

// "Result is cef"

let test2 =

let removalAction = (subtract "abc") ++ (subtract "abc") ++ (subtract "abc")

removalAction |> applyTo "abcdef" |> printfn "Result is %s"

// "Result is "

The way to think about this approach is that, in a sense, we are modelling actions rather than data. We have a list of CharsToRemove actions,

then we combine them into a single “big” CharsToRemove action,

and then we execute that single action at the end, after we have finished the intermediate manipulations.

We’ll see another example of this shortly, but you might be thinking at this point: “this sounds a bit like functions, doesn’t it?” To which I will say “yes, it does!”

In fact rather than creating this CharsToRemove data structure, we could have just partially applied the original subtractChars function, as shown below:

(Note that we reverse the parameters to make partial application easier)

// reverse for partial application

let subtract str charsToSubtract =

subtractChars charsToSubtract str

let removalAction = subtract "abd"

"abcdef" |> removalAction |> printfn "Result is %s"

// "Result is cef"

And now we don’t even need a special applyTo function.

But when we have more than one of these subtraction functions, what do we do?

Each of these partially applied functions has signature string -> string, so how can we “add” them together?

(subtract "abc") + (subtract "abc") + (subtract "abc") = ?

The answer is function composition, of course!

let removalAction2 = (subtract "abc") >> (subtract "abc") >> (subtract "abc")

removalAction2 "abcdef" |> printfn "Result is %s"

// "Result is def"

This is the functional equivalent of creating the CharsToRemove data structure.

The “data structure as action” and function approach are not exactly the same – the CharsToRemove approach may be more efficient, for example, because it uses a set, and is only applied to strings at the end – but they both achieve the same goal.

Which one is better depends on the particular problem you’re working on.

I’ll have more to say on functions and monoids in the next post.

Now to the last requirement for a monoid: identity.

As we have seen, identity is not always needed, but it is nice to have if you might be dealing with empty lists.

For numeric values, finding an identity for an operation is generally easy, whether it be 0 (addition), 1 (multiplication) or Int32.MinValue (max).

And this carries over to structures that contain only numeric values as well – just set all values to their appropriate identity. The CustomerStats type from the previous post demonstrates that nicely.

But what if you have objects that are not numeric? How can you create a “zero” or identity element if there is no natural candidate?

The answer is: you just make one up.

Seriously!

We have already seen an example of this in the previous post, when we added an EmptyOrder case to the OrderLine type:

type OrderLine =

| Product of ProductLine

| Total of TotalLine

| EmptyOrder

Let’s look at this more closely. We performed two steps:

- First, we created a new case and added it to the list of alternatives for an

OrderLine(as shown above). - Second, we adjusted the

addLinefunction to take it into account (as shown below).

let addLine orderLine1 orderLine2 =

match orderLine1,orderLine2 with

// is one of them zero? If so, return the other one

| EmptyOrder, _ -> orderLine2

| _, EmptyOrder -> orderLine1

// logic for other cases ...

That’s all there is to it.

The new, augmented type consists of the old order line cases, plus the new EmptyOrder case, and so it can reuse much of the behavior of the old cases.

In particular, can you see that the new augmented type follows all the monoid rules?

- A pair of values of the new type can be added to get another value of the new type (closure)

- If the combination order didn’t matter for the old type, then it still doesn’t matter for the new type (associativity)

- And finally… this extra case now gives us an identity for the new type.

We could do the same thing with the other semigroups we’ve seen.

For example, we noted earlier that strictly positive numbers (under addition) didn’t have an identity; they are only a semigroup.

If we wanted to create a zero using the “augmentation with extra case” technique (rather than just using 0!) we would

first define a special Zero case (not an integer), and then create an addPositive function that can handle it, like this:

type PositiveNumberOrIdentity =

| Positive of int

| Zero

let addPositive i1 i2 =

match i1,i2 with

| Zero, _ -> i2

| _, Zero -> i1

| Positive p1, Positive p2 -> Positive (p1 + p2)

Admittedly, PositiveNumberOrIdentity is a contrived example, but you can see how this same approach would work for any situation where you have “normal” values and a special, separate, zero value.

There are a few drawbacks to this:

- We have to deal with two cases now: the normal case and the zero case.

- We have to create custom types and custom addition functions

Unfortunately, there’s nothing you can do about the first issue. If you have a system with no natural zero, and you create an artificial one, then you will indeed always have to deal with two cases.

But there is something you can do about the second issue! Rather than create a new custom type over and over, perhaps can we create a generic type that has two cases: one for all normal values and one for the artificial zero, like this:

type NormalOrIdentity<'T> =

| Normal of 'T

| Zero

Does this type look familiar? It’s just the Option type in disguise!

In other words, any time we need an identity which is outside the normal set of values, we can use Option.None to represent it. And then Option.Some is used for all the other “normal” values.

Another benefit of using Option is that we can also write a completely generic “add” function as well. Here’s a first attempt:

let optionAdd o1 o2 =

match o1, o2 with

| None, _ -> o2

| _, None -> o1

| Some s1, Some s2 -> Some (s1 + s2)

The logic is straightforward. If either option is None, the other option is returned. If both are Some, then they are unwrapped, added together, and then wrapped in a Some again.

But the + in the last line makes assumptions about the types that we are adding. Better to pass in the addition function explicitly, like this:

let optionAdd f o1 o2 =

match o1, o2 with

| None, _ -> o2

| _, None -> o1

| Some s1, Some s2 -> Some (f s1 s2)

In practice, this would used with partial application to bake in the addition function.

So now we have another important tip:

- DESIGN TIP: To get identity for an operation, create a special case in a discriminated union, or, even simpler, just use Option.

So here is the Positive Number example again, now using the Option type.

type PositiveNumberOrIdentity = int option

let addPositive = optionAdd (+)

Much simpler!

Notice that we pass in the “real” addition function as a parameter to optionAdd so that it is baked in.

In other situations, you would do the same with the relevant aggregation function that is associated with the semigroup.

As a result of this partial application, addPositive has the signature: int option -> int option -> int option, which is exactly what we would expect from a monoid addition function.

In other words, optionAdd turns any function 'a -> 'a -> 'a into the same function, but “lifted” to the option type, that is, having a signature 'a option -> 'a option -> 'a option .

So, let’s test it! Some test code might look like this:

// create some values

let p1 = Some 1

let p2 = Some 2

let zero = None

// test addition

addPositive p1 p2

addPositive p1 zero

addPositive zero p2

addPositive zero zero

You can see that unfortunately we do have to wrap the normal values in Some in order to get the None as identity.

That sounds tedious but in practice, it is easy enough. The code below shows how we might handle the two distinct cases when summing a list. First how to sum a non-empty list, and then how to sum an empty list.

[1..10]

|> List.map Some

|> List.fold addPositive zero

[]

|> List.map Some

|> List.fold addPositive zero

While we’re at it, let’s also revisit the ValidationResult type that we described earlier when talking about using lists to get closure. Here it is again:

type ValidationResult =

| Success

| Failure of string list

Now that we’ve got some insight into the positive integer case, let’s look at this type from a different angle as well.

The type has two cases. One case holds data that we care about, and the other case holds no data. But the data we really care about are the error messages, not the success. As Leo Tolstoy nearly said “All validation successes are alike; each validation failure is a failure in its own way.”

So, rather than thinking of it as a “Result”, let’s think of the type as storing failures, and rewrite it like this instead, with the failure case first:

type ValidationFailure =

| Failure of string list

| Success

Does this type appear familiar now?

Yes! It’s the option type again! Can we never get away from the darn thing?

Using the option type, we can simplify the design of the ValidationFailure type to just this:

type ValidationFailure = string list option

The helper to convert a string into the failure case is now just Some with a list:

let fail str =

Some [str]

And the “add” function can reuse optionAdd, but this time with list concatenation as the underlying operation:

let addFailure f1 f2 = optionAdd (@) f1 f2

Finally, the “zero” that was the Success case in the original design now simply becomes None in the new design.

Here’s all the code, plus tests

module MonoidalValidationOption =

type ValidationFailure = string list option

// helper to convert a string into the failure case

let fail str =

Some [str]

let validateBadWord badWord (name:string) =

if name.Contains(badWord) then

fail ("string contains a bad word: " + badWord)

else

None

let validateLength maxLength name =

if String.length name > maxLength then

fail "string is too long"

else

None

let optionAdd f o1 o2 =

match o1, o2 with

| None, _ -> o2

| _, None -> o1

| Some s1, Some s2 -> Some (f s1 s2)

/// add two results using optionAdd

let addFailure f1 f2 = optionAdd (@) f1 f2

// define the Zero

let Success = None

module MonoidalValidationOptionTest =

open MonoidalValidationOption

let test1 =

let result1 = Success

let result2 = Success

addFailure result1 result2

|> printfn "Result is %A"

// Result is <null>

let test2 =

let result1 = Success

let result2 = fail "string is too long"

addFailure result1 result2

|> printfn "Result is %A"

// Result is Some ["string is too long"]

let test3 =

let result1 = fail "string is null or empty"

let result2 = fail "string is too long"

addFailure result1 result2

|> printfn "Result is %A"

// Result is Some ["string is null or empty"; "string is too long"]

let test4 =

let validationResults str =

[

validateLength 10

validateBadWord "monad"

validateBadWord "cobol"

]

|> List.map (fun validate -> validate str)

"cobol has native support for monads"

|> validationResults

|> List.reduce addFailure

|> printfn "Result is %A"

// Result is Some

// ["string is too long"; "string contains a bad word: monad";

// "string contains a bad word: cobol"]

let test5 =

let validationResults str =

[]

|> List.map (fun validate -> validate str)

"cobol has native support for monads"

|> validationResults

|> List.fold addFailure Success

|> printfn "Result is %A"

// Result is <null>

Let’s pause for a second and see what we have covered so far.

Here are all the design tips together:

- To easily create a monoidal type, make sure that each field of the type is also a monoid.

- To enable closure for a non-numeric type, replace single items with lists (or a similar data structure).

- To get associativity for an operation, try to move the operation into the object.

- To get identity for an operation, create a special case in a discriminated union, or, even simpler, just use Option.

In the next two sections, we’ll apply these tips to two of the non-monoids that we have seen in previous posts: “average” and “most frequent word”.

So now we have the toolkit that will enable us to deal with the thorny case of averages.

Here’s a simple implementation of a pairwise average function:

let avg i1 i2 =

float (i1 + i2) / 2.0

// test

avg 4 5 |> printfn "Average is %g"

// Average is 4.5

As we mentioned briefly in the first post, avg fails on all three monoid requirements!

First, it is not closed. Two ints that are combined together using avg do not result in another int.

Second, even if it was closed, avg is not associative, as we can see by defining a similar float function avgf:

let avgf i1 i2 =

(i1 + i2) / 2.0

// test

avgf (avgf 1.0 3.0) 5.0 |> printfn "Average from left is %g"

avgf 1.0 (avgf 3.0 5.0) |> printfn "Average from right is %g"

// Average from left is 3.5

// Average from right is 2.5

Finally, there is no identity.

What number, when averaged with any other number, returns the original value? Answer: none!

So let’s apply the design tips to see if they help us come up with a solution.

- To easily create a monoidal type, make sure that each field of the type is also a monoid.

Well, “average” is a mathematical operation, so we could expect that a monoidal equivalent would also be based on numbers.

- To enable closure for a non-numeric type, replace single items with lists.

This looks at first glance like it won’t be relevant, so we’ll skip this for now.

- To get associativity for an operation, try to move the operation into the object.

Here’s the crux! How do we convert “average” from a verb (an operation) to a noun (a data structure)?

The answer is that we create a structure that is not actually an average, but a “delayed average” – everything you need to make an average on demand.

That is, we need a data structure with two components: a total, and a count. With these two numbers we can calculate an average as needed.

// store all the info needed for an average

type Avg = {total:int; count:int}

// add two Avgs together

let addAvg avg1 avg2 =

{total = avg1.total + avg2.total;

count = avg1.count + avg2.count}

The good thing about this, is that structure stores ints, not floats, so we don’t need to worry about loss of precision or associativity of floats.

The last tip is:

- To get identity for an operation, create a special case in a discriminated union, or, even simpler, just use Option.

In this case, the tip is not needed, as we can easily create a zero by setting the two components to be zero:

let zero = {total=0; count=0}

We could also have used None for the zero, but it seems like overkill in this case. If the list is empty, the Avg result is valid, even though we can’t do the division.

Once we have had this insight into the data structure, the rest of the implementation follows easily. Here is all the code, plus some tests:

module Average =

// store all the info needed for an average

type Avg = {total:int; count:int}

// add two Avgs together

let addAvg avg1 avg2 =

{total = avg1.total + avg2.total;

count = avg1.count + avg2.count}

// inline version of add

let (++) = addAvg

// construct an average from a single number

let avg n = {total=n; count=1}

// calculate the average from the data.

// return 0 for empty lists

let calcAvg avg =

if avg.count = 0

then 0.0

else float avg.total / float avg.count

// alternative - return None for empty lists

let calcAvg2 avg =

if avg.count = 0

then None

else Some (float avg.total / float avg.count)

// the identity

let zero = {total=0; count=0}

// test

addAvg (avg 4) (avg 5)

|> calcAvg

|> printfn "Average is %g"

// Average is 4.5

(avg 4) ++ (avg 5) ++ (avg 6)

|> calcAvg

|> printfn "Average is %g"

// Average is 5

// test

[1..10]

|> List.map avg

|> List.reduce addAvg

|> calcAvg

|> printfn "Average is %g"

// Average is 5.5

In the code above, you can see that I created a calcAvg function that uses the Avg structure to calculate a (floating point) average. One nice thing

about this approach is that we can delay having to make a decision about what to do with a zero divisor. We can just return 0, or alternatively None, or

we can just postpone the calculation indefinitely, and only generate the average at the last possible moment, on demand!

And of course, this implementation of “average” has the ability to do incremental averages. We get this for free because it is a monoid.

That is, if I have already calculated the average of a million numbers, and I want to add one more, I don’t have to recalculate everything, I can just add the new number to the totals so far.

If you have ever been responsible for managing any servers or services, you will be aware of the importance of logging and monitoring metrics, such as CPU, I/O, etc.

One of the questions you often face then is how to design your metrics. Do you want kilobytes per second, or just total kilobytes since the server started. Visitors per hour, or total visitors?

If you look at some guidelines when creating metrics you will see the frequent recommendation to only track metrics that are counters, not rates.

The advantage of counters is that (a) missing data doesn’t affect the big picture, and (b) they can be aggregated in many ways after the fact – by minute, by hour, as a ratio with something else, and so on.

Now that you have worked through this series, you can see that the recommendation can really be rephrased as metrics should be monoids.

The work we did in the code above to transform “average” into two components, “total” and “count”, is exactly what you want to do to make a good metric.

Averages and other rates are not monoids, but “total” and “count” are, and then “average” can be calculated from them at your leisure.

In the last post, we implemented a “most frequent word” function, but found that it wasn’t a monoid homomorphism. That is,

mostFrequentWord(text1) + mostFrequentWord(text2)

did not give the same result as:

mostFrequentWord( text1 + text2 )

Again, we can use the design tips to fix this up so that it works.

The insight here is again to delay the calculation until the last minute, just as we did in the “average” example.

Rather than calculating the most frequent word upfront then, we create a data structure that stores all the information that we need to calculate the most frequent word later.

module FrequentWordMonoid =

open System

open System.Text.RegularExpressions

type Text = Text of string

let addText (Text s1) (Text s2) =

Text (s1 + s2)

// return a word frequency map

let wordFreq (Text s) =

Regex.Matches(s,@"\S+")

|> Seq.cast<Match>

|> Seq.map (fun m -> m.ToString())

|> Seq.groupBy id

|> Seq.map (fun (k,v) -> k,Seq.length v)

|> Map.ofSeq

In the code above we have a new function wordFreq, that returns a Map<string,int> rather just a single word.

That is, we are now working with dictionaries, where each slot has a word and its associated frequency.

Here is a demonstration of how it works:

module FrequentWordMonoid =

// code from above

let page1() =

List.replicate 1000 "hello world "

|> List.reduce (+)

|> Text

let page2() =

List.replicate 1000 "goodbye world "

|> List.reduce (+)

|> Text

let page3() =

List.replicate 1000 "foobar "

|> List.reduce (+)

|> Text

let document() =

[page1(); page2(); page3()]

// show some word frequency maps

page1() |> wordFreq |> printfn "The frequency map for page1 is %A"

page2() |> wordFreq |> printfn "The frequency map for page2 is %A"

//The frequency map for page1 is map [("hello", 1000); ("world", 1000)]

//The frequency map for page2 is map [("goodbye", 1000); ("world", 1000)]

document()

|> List.reduce addText

|> wordFreq

|> printfn "The frequency map for the document is %A"

//The frequency map for the document is map [

// ("foobar", 1000); ("goodbye", 1000);

// ("hello", 1000); ("world", 2000)]

With this map structure in place, we can create a function addMap to add two maps. It simply merges the frequency counts of the words from both maps.

module FrequentWordMonoid =

// code from above

// define addition for the maps

let addMap map1 map2 =

let increment mapSoFar word count =

match mapSoFar |> Map.tryFind word with

| Some count' -> mapSoFar |> Map.add word (count + count')

| None -> mapSoFar |> Map.add word count

map2 |> Map.fold increment map1

And when we have combined all the maps together, we can then calculate the most frequent word by looping through the map and finding the word with the largest frequency.

module FrequentWordMonoid =

// code from above

// as the last step,

// get the most frequent word in a map

let mostFrequentWord map =

let max (candidateWord,maxCountSoFar) word count =

if count > maxCountSoFar

then (word,count)

else (candidateWord,maxCountSoFar)

map |> Map.fold max ("None",0)

So, here are the two scenarios revisited using the new approach.

The first scenario combines all the pages into a single text, then applies wordFreq to get a frequency map, and applies mostFrequentWord to get the most frequent word.

The second scenario applies wordFreq to each page separately to get a map for each page.

These maps are then combined with addMap to get a single global map. Then mostFrequentWord is applied as the last step, as before.

module FrequentWordMonoid =

// code from above

document()

|> List.reduce addText

|> wordFreq

// get the most frequent word from the big map

|> mostFrequentWord

|> printfn "Using add first, the most frequent word and count is %A"

//Using add first, the most frequent word and count is ("world", 2000)

document()

|> List.map wordFreq

|> List.reduce addMap

// get the most frequent word from the merged smaller maps

|> mostFrequentWord

|> printfn "Using map reduce, the most frequent and count is %A"

//Using map reduce, the most frequent and count is ("world", 2000)

If you run this code, you will see that you now get the same answer.

This means that wordFreq is indeed a monoid homomorphism, and is suitable for running in parallel, or incrementally.

We’ve seen a lot of code in this post, but it has all been focused on data structures.

However, there is nothing in the definition of a monoid that says that the things to be combined have to be data structures – they could be anything at all.

In the next post we’ll look at monoids applied to other objects, such as types, functions, and more.

In the examples above, I have made frequent use of @ to “add” two lists in the same way that + adds two numbers.

I did this to highlight the analogies with other monoidal operations such as numeric addition and string concatenation.

I hope that it is clear that the code samples above are meant to be teaching examples, not necessarily good models for the kind of real-world, battle-hardened, and all-too-ugly code you need in a production environment.

A couple of people have pointed out that using List append (@) should be avoided in general. This is because the entire first list needs to be copied, which is not very efficient.

By far the best way to add something to a list is to add it to the front using the so-called “cons” mechanism, which in F# is just ::. F# lists are implemented as linked lists, so

adding to the front is very cheap.

The problem with using this approach is that it is not symmetrical – it doesn’t add two lists together, just a list and an element. This means that it cannot be used as the “add” operation in a monoid.

If you don’t need the benefits of a monoid, such as divide and conquer, then that is a perfectly valid design decision. No need to sacrifice performance for a pattern that you are not going to benefit from.

The other alternative to using @ is to not use lists in the first place!

In the ValidationResult design, I used a list to hold the error results so that we could get easy accumulation of the results.

But I only chose the list type because it is really the default collection type in F#.

I could have equally well have chosen sequences, or arrays, or sets. Almost any other collection type would have done the job just as well.

But not all types will have the same performance. For example, combining two sequences is a lazy operation. You don’t have to copy all the data; you just enumerate one sequence, then the other. So that might be faster perhaps?

Rather than guessing, I wrote a little test script to measure performance at various list sizes, for various collection types.

I have chosen a very simple model: we have a list of objects, each of which is a collection containing one item. We then reduce this list of collections into a single giant collection using the appropriate monoid operation. Finally, we iterate over the giant collection once.

This is very similar to the ValidationResult design, where we would combine all the results into a single list of results, and then (presumably) iterate over them to show the errors.

It is also similar to the “most frequent word” design, above, where we combine all the individual frequency maps into a single frequency map, and then iterate over it to find the most frequent word.

In that case, of course, we were using map rather than list, but the set of steps is the same.

Ok, here’s the code:

module Performance =

let printHeader() =

printfn "Label,ListSize,ReduceAndIterMs"

// time the reduce and iter steps for a given list size and print the results

let time label reduce iter listSize =

System.GC.Collect() //clean up before starting

let stopwatch = System.Diagnostics.Stopwatch()

stopwatch.Start()

reduce() |> iter

stopwatch.Stop()

printfn "%s,%iK,%i" label (listSize/1000) stopwatch.ElapsedMilliseconds

let testListPerformance listSize =

let lists = List.init listSize (fun i -> [i.ToString()])

let reduce() = lists |> List.reduce (@)

let iter = List.iter ignore

time "List.@" reduce iter listSize

let testSeqPerformance_Append listSize =

let seqs = List.init listSize (fun i -> seq {yield i.ToString()})

let reduce() = seqs |> List.reduce Seq.append

let iter = Seq.iter ignore

time "Seq.append" reduce iter listSize

let testSeqPerformance_Yield listSize =

let seqs = List.init listSize (fun i -> seq {yield i.ToString()})

let reduce() = seqs |> List.reduce (fun x y -> seq {yield! x; yield! y})

let iter = Seq.iter ignore

time "seq(yield!)" reduce iter listSize

let testArrayPerformance listSize =

let arrays = List.init listSize (fun i -> [| i.ToString() |])

let reduce() = arrays |> List.reduce Array.append

let iter = Array.iter ignore

time "Array.append" reduce iter listSize

let testResizeArrayPerformance listSize =

let resizeArrays = List.init listSize (fun i -> new ResizeArray<string>( [i.ToString()] ) )

let append (x:ResizeArray<_>) y = x.AddRange(y); x

let reduce() = resizeArrays |> List.reduce append

let iter = Seq.iter ignore

time "ResizeArray.append" reduce iter listSize

Let’s go through the code quickly:

- The

timefunction times the reduce and iteration steps. It deliberately does not test how long it takes to create the collection. I do perform a GC before starting, but in reality, the memory pressure that a particular type or algorithm causes is an important part of the decision to use it (or not). Understanding how GC works is an important part of getting performant code. - The

testListPerformancefunction sets up the list of collections (lists in this case) and also thereduceanditerfunctions. It then runs the timer onreduceanditer. - The other functions do the same thing, but with sequences, arrays, and ResizeArrays (standard .NET Lists).

Out of curiosity, I thought I’d test two ways of merging sequences, one using the standard library

function

Seq.appendand the other using twoyield!s in a row. - The

testResizeArrayPerformanceuses ResizeArrays and adds the right list to the left one. The left one mutates and grows larger as needed, using a growth strategy that keeps inserts efficient.

Now let’s write code to check the performance on various sized lists. I chose to start with a count of 2000 and move by increments of 4000 up to 50000.

open Performance

printHeader()

[2000..4000..50000]

|> List.iter testArrayPerformance

[2000..4000..50000]

|> List.iter testResizeArrayPerformance

[2000..4000..50000]

|> List.iter testListPerformance

[2000..4000..50000]

|> List.iter testSeqPerformance_Append

[2000..4000..50000]

|> List.iter testSeqPerformance_Yield

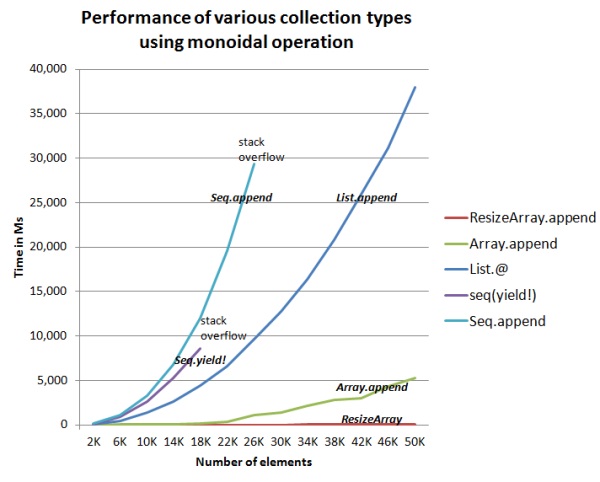

I won’t list all the detailed output – you can run the code for yourself – but here is a chart of the results.

There are a few things to note:

- The two sequence-based examples crashed with stack overflows. The

yield!was about 30% faster thanSeq.append, but also ran out of stack faster. - List.append didn’t run out of stack, but got much slower as the lists got larger.

- Array.append was fast, and increases more slowly with the size of the list

- ResizeArray was fastest of all, and didn’t break a sweat even with large lists.

For the three collection types that didn’t crash, I also timed them for a list of 100K items. The results were:

- List = 150,730 ms

- Array = 26,062 ms

- ResizeArray = 33 ms

A clear winner there, then.

What conclusion can we draw from this little experiment?

First, you might have all sorts of questions, such as: Were you running in debug or release mode? Did you have optimization turned on? What about using parallelism to increase performance? And no doubt, there will be comments saying “why did you use technique X, technique Y is so much better”.

But here’s the conclusion I would like to make:

- You cannot draw any conclusion from these results!

Every situation is different and requires a different approach:

- If you are working with small data sets you might not care about performance anyway. In this case I would stick with lists – I’d rather not sacrifice pattern matching and immutability unless I have to.

- The performance bottleneck might not be in the list addition code. There is no point working on optimizing the list addition if you are actually spending all your time on disk I/O or network delays. A real-world version of the word frequency example might actually spend most of its time doing reading from disk, or parsing, rather than adding lists.

- If you working at the scale of Google, Twitter, or Facebook, you really need to go and hire some algorithm experts.

The only principles that we can take away from any discussion on optimization and performance are:

- A problem must be dealt with in its own context. The size of the data being processed, the type of hardware, the amount of memory, and so on. All these will make a difference to your performance. What works for me may not work for you, which is why…

- You should always measure, not guess. Don’t make assumptions about where your code is spending its time – learn to use a profiler! There are some good examples of using a profiler here and here.

- Be wary of micro-optimizations. Even if your profiler shows that your sorting routine spends all its time in comparing strings, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you need to improve your string comparison function. You might be better off improving your algorithm so that you don’t need to do so many comparisons in the first place. Premature optimization and all that.

Twitter

Twitter