Understanding Parser Combinators

UPDATE: Slides and video from my talk on this topic

In this series, we’ll look at how so-called “applicative parsers” work. In order to understand something, there’s nothing like building it for yourself, and so we’ll create a basic parser library from scratch, and then some useful “parser combinators”, and then finish off by building a complete JSON parser.

Now terms like “applicative parsers” and “parser combinators” can make this approach seem complicated, but rather than attempting to explain these concepts up front, we’ll just dive in and start coding.

We’ll build up to the complex stuff incrementally via a series of implementations, where each implementation is only slightly different from the previous one. By using this approach, I hope that at each stage the design and concepts will be easy to understand, and so by the end of this series, parser combinators will have become completely demystified.

There will be four posts in this series:

- In this, the first post, we’ll look at the basic concepts of parser combinators and build the core of the library.

- In the second post, we’ll build up a useful library of combinators.

- In the third post, we’ll work on providing helpful error messages.

- In the last post, we’ll build a JSON parser using this parser library.

Obviously, the focus here will not be on performance or efficiency, but I hope that it will give you the understanding that will then enable you to use libraries like FParsec effectively. And by the way, a big thank you to Stephan Tolksdorf, who created FParsec. You should make it your first port of call for all your .NET parsing needs!

To start with, let’s create something that just parses a single, hard-coded, character, in this case, the letter “A”. You can’t get much simpler than that!

Here is how it works:

- The input to a parser is a stream of characters. We could use something complicated, but for now we’ll just use a

string. - If the stream is empty, then return a pair consisting of

falseand an empty string. - If the first character in the stream is an

A, then return a pair consisting oftrueand the remaining stream of characters. - If the first character in the stream is not an

A, then returnfalseand the (unchanged) original stream of characters.

Here’s the code:

let parseA str =

if String.IsNullOrEmpty(str) then

(false,"")

else if str.[0] = 'A' then

let remaining = str.[1..]

(true,remaining)

else

(false,str)

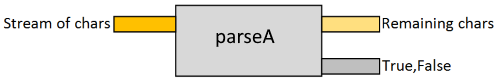

The signature of parseA is:

val parseA :

string -> (bool * string)

which tells us that the input is a string, and the output is a pair consisting of the boolean result and another string (the remaining input), like this:

Let’s test it now – first with good input:

let inputABC = "ABC"

parseA inputABC

The result is:

(true, "BC")

As you can see, the A has been consumed and the remaining input is just "BC".

And now with bad input:

let inputZBC = "ZBC"

parseA inputZBC

which gives the result:

(false, "ZBC")

And in this case, the first character was not consumed and the remaining input is still "ZBC".

So, there’s an incredibly simple parser for you. If you understand that, then everything that follows will be easy!

Let’s refactor so that we can pass in the character we want to match, rather than having it be hard coded.

And this time, rather than returning true or false, we’ll return a message indicating what happened.

We’ll call the function pchar for “parse char”. This will become the fundamental building block of all our parsers. Here’s the code for our first attempt:

let pchar (charToMatch,str) =

if String.IsNullOrEmpty(str) then

let msg = "No more input"

(msg,"")

else

let first = str.[0]

if first = charToMatch then

let remaining = str.[1..]

let msg = sprintf "Found %c" charToMatch

(msg,remaining)

else

let msg = sprintf "Expecting '%c'. Got '%c'" charToMatch first

(msg,str)

This code is just like the previous example, except that the unexpected character is now shown in the error message.

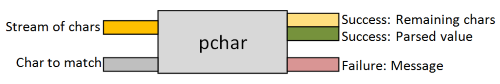

The signature of pchar is:

val pchar :

(char * string) -> (string * string)

which tells us that the input is a pair of (string,character to match) and the output is a pair consisting of the (string) result and another string (the remaining input).

Let’s test it now – first with good input:

let inputABC = "ABC"

pchar('A',inputABC)

The result is:

("Found A", "BC")

As before, the A has been consumed and the remaining input is just "BC".

And now with bad input:

let inputZBC = "ZBC"

pchar('A',inputZBC)

which gives the result:

("Expecting 'A'. Got 'Z'", "ZBC")

And again, as before, the first character was not consumed and the remaining input is still "ZBC".

If we pass in Z, then the parser does succeed:

pchar('Z',inputZBC) // ("Found Z", "BC")

We want to be able to tell the difference between a successful match and a failure, and returning a stringly-typed message is not very helpful, so let’s use a choice type (aka sum type, aka discriminated union) to indicate the difference. I’ll call it ParseResult:

type ParseResult<'a> =

| Success of 'a

| Failure of string

The Success case is generic and can contain any value. The Failure case contains an error message.

For more on using this Success/Failure approach, see my talk on functional error handling.

We can now rewrite the parser to return one of the Result cases, like this:

let pchar (charToMatch,str) =

if String.IsNullOrEmpty(str) then

Failure "No more input"

else

let first = str.[0]

if first = charToMatch then

let remaining = str.[1..]

Success (charToMatch,remaining)

else

let msg = sprintf "Expecting '%c'. Got '%c'" charToMatch first

Failure msg

The signature of pchar is now:

val pchar :

(char * string) -> ParseResult<char * string>

which tells us that the the output is now a ParseResult (which in the Success case, contains the matched char and the remaining input string).

Let’s test it again – first with good input:

let inputABC = "ABC"

pchar('A',inputABC)

The result is:

Success ('A', "BC")

As before, the A has been consumed and the remaining input is just "BC". We also get the actual matched char (A in this case).

And now with bad input:

let inputZBC = "ZBC"

pchar('A',inputZBC)

which gives the result:

Failure "Expecting 'A'. Got 'Z'"

And in this case, the Failure case is returned with the appropriate error message.

This is a diagram of the function’s inputs and outputs now:

In the previous implementation, the input to the function has been a tuple – a pair. This requires you to pass both inputs at once. In functional languages like F#, it’s more idiomatic to use a curried version, like this:

let pchar charToMatch str =

if String.IsNullOrEmpty(str) then

Failure "No more input"

else

let first = str.[0]

if first = charToMatch then

let remaining = str.[1..]

Success (charToMatch,remaining)

else

let msg = sprintf "Expecting '%c'. Got '%c'" charToMatch first

Failure msg

Can you see the difference? The only difference is in the first line, and even then it is subtle.

Here’s the uncurried (tuple) version:

let pchar (charToMatch,str) =

...

And here’s the curried version:

let pchar charToMatch str =

...

The difference is much more obvious when you look at the type signatures. Here’s the signature for the uncurried (tuple) version:

val pchar :

(char * string) -> Result<char * string>

// ^ tuple

And here’s the signature for the curried version:

val pchar :

char -> string -> Result<char * string>

// ^ curried

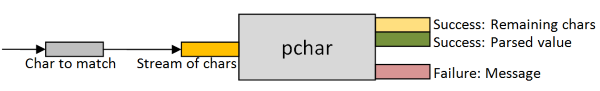

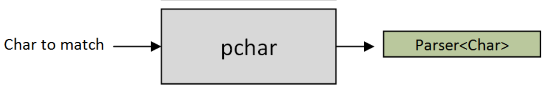

Here is the curried version of pchar represented as a diagram:

If you are unclear on how currying works, I have a post about it here, but basically it means that a multi-parameter function can be written as a series of one-parameter functions.

In other words, this two-parameter function:

let add x y =

x + y

which has the signature:

val add : x:int -> y:int -> int

can be written as an equivalent one-parameter function that returns a lambda, like this:

let add x =

fun y -> x + y // return a lambda

or as a function that returns an inner function, like this:

let add x =

let innerFn y = x + y

innerFn // return innerFn

In the second case, when an inner function is used, the signature looks slightly different:

val add : x:int -> (int -> int)

but the parentheses around the last parameter can be ignored. The signature, for all practical purposes, is the same as the original one:

// original (automatic currying of two parameter function)

val add : x:int -> y:int -> int

// explicit currying with inner function

val add : x:int -> (int -> int)

We can take advantage of currying and rewrite the parser as a one-parameter function (where the parameter is charToMatch) that returns a inner function.

Here’s the new implementation, with the inner function cleverly named innerFn:

let pchar charToMatch =

// define a nested inner function

let innerFn str =

if String.IsNullOrEmpty(str) then

Failure "No more input"

else

let first = str.[0]

if first = charToMatch then

let remaining = str.[1..]

Success (charToMatch,remaining)

else

let msg = sprintf "Expecting '%c'. Got '%c'" charToMatch first

Failure msg

// return the inner function

innerFn

The type signature for this implementation looks like this:

val pchar :

charToMatch:char -> (string -> ParseResult<char * string>)

which is functionally equivalent to the signature of the previous version. In other words, both of the implementations below are identical from the callers point of view:

// two-parameter implementation

let pchar charToMatch str =

...

// one-parameter implementation with inner function

let pchar charToMatch =

let innerFn str =

...

// return the inner function

innerFn

What’s nice about the curried implementation is that we can partially apply the character we want to parse, to get a new function, like this:

let parseA = pchar 'A'

We can now supply the second “input stream” parameter later:

let inputABC = "ABC"

parseA inputABC //=> Success ('A', "BC")

let inputZBC = "ZBC"

parseA inputZBC //=> Failure "Expecting 'A'. Got 'Z'"

At this point, let’s stop and review what is going on:

- The

pcharfunction has two inputs - We can provide one input (the char to match) and this results in a function being returned.

- We can then provide the second input (the stream of characters) to this parsing function, and this creates the final

Resultvalue.

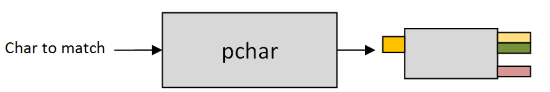

Here’s a diagram of pchar again, but this time with the emphasis on partial application:

It’s very important that you understand this logic before moving on, because the rest of the post will build on this basic design.

If we look at parseA (from the example above) we can see that it has a function type:

val parseA : string -> ParseResult<char * string>

That type is a bit complicated to use, so let’s encapsulate it in a “wrapper” type called Parser, like this:

type Parser<'T> = Parser of (string -> ParseResult<'T * string>)

By encapsulating it, we’ll go from this design:

to this design, where it returns a Parser value:

What are the benefits of having this extra type, rather than working with the “raw” string -> ParseResult function directly?

- It’s always good practice to use types to model the domain, and in this domain we are dealing with “parsers” not functions (even though they are the same thing behind the scenes).

- It makes the type inference easier and helps to make the parser combinators (that we will create later) more understandable (e.g. a combinator that takes two “Parser” parameters is clear, but a combinator taking two parameters of type

string -> ParseResult<'a * string>is hard to read). - Finally, it supports information hiding (via an abstract data type), so that we can later add metadata such as label/row/column, etc, without breaking any clients.

The change to the implementation is straightforward. We just need to change the way the inner function is returned.

That is, from this:

let pchar charToMatch =

let innerFn str =

...

// return the inner function

innerFn

to this:

let pchar charToMatch =

let innerFn str =

...

// return the "wrapped" inner function

Parser innerFn

Ok, now let’s test again:

let parseA = pchar 'A'

let inputABC = "ABC"

parseA inputABC // compiler error

But now we get a compiler error:

error FS0003: This value is not a function and cannot be applied.

And of course that is because the function is wrapped in the Parser data structure! It’s not longer directly accessible.

So now we need a helper function that can extract the inner function and run it against the input stream. Let’s call it run! Here’s its implementation:

let run parser input =

// unwrap parser to get inner function

let (Parser innerFn) = parser

// call inner function with input

innerFn input

And now we can run the parseA parser against various inputs again:

let inputABC = "ABC"

run parseA inputABC // Success ('A', "BC")

let inputZBC = "ZBC"

run parseA inputZBC // Failure "Expecting 'A'. Got 'Z'"

That’s it! We’ve got a basic Parser type! I hope that this all makes sense so far.

That last implementation is good enough for basic parsing logic. We’ll revisit it later, but now let’s move up a level and develop some ways of combining parsers together – the “parser combinators” mentioned at the beginning.

We’ll start with combining two parsers in sequence. For example, say that we want a parser that matches “A” and then “B”. We could try writing something like this:

let parseA = pchar 'A'

let parseB = pchar 'B'

let parseAThenB = parseA >> parseB

but that gives us a compiler error, as the output of parseA does not match the input of parseB, and so they cannot be composed like that.

If you are familiar with functional programming patterns, the need to chain a sequence of wrapped types together like this happens frequently, and the solution is a bind function.

However, in this case, I won’t implement bind but will instead go straight to an andThen implementation.

The implementation logic will be as follows:

- Run the first parser.

- If there is a failure, return.

- Otherwise, run the second parser with the remaining input.

- If there is a failure, return.

- If both parsers succeed, return a pair (tuple) that contains both parsed values.

Here’s the code for andThen:

let andThen parser1 parser2 =

let innerFn input =

// run parser1 with the input

let result1 = run parser1 input

// test the result for Failure/Success

match result1 with

| Failure err ->

// return error from parser1

Failure err

| Success (value1,remaining1) ->

// run parser2 with the remaining input

let result2 = run parser2 remaining1

// test the result for Failure/Success

match result2 with

| Failure err ->

// return error from parser2

Failure err

| Success (value2,remaining2) ->

// combine both values as a pair

let newValue = (value1,value2)

// return remaining input after parser2

Success (newValue,remaining2)

// return the inner function

Parser innerFn

The implementation follows the logic described above.

We’ll also define an infix version of andThen so that we can use it like regular >> composition:

let ( .>>. ) = andThen

Note: the parentheses are needed to define a custom operator, but are not needed in the infix usage.

If we look at the signature of andThen:

val andThen :

parser1:Parser<'a> -> parser2:Parser<'b> -> Parser<'a * 'b>

we can see that it works for any two parsers, and they can be of different types ('a and 'b).

Let’s test it and see if it works!

First, create the compound parser:

let parseA = pchar 'A'

let parseB = pchar 'B'

let parseAThenB = parseA .>>. parseB

If you look at the types, you can see that all three values have type Parser:

val parseA : Parser<char>

val parseB : Parser<char>

val parseAThenB : Parser<char * char>

parseAThenB is of type Parser<char * char> meaning that the parsed value is a pair of chars.

Now since the combined parser parseAThenB is just another Parser, we can use run with it as before.

run parseAThenB "ABC" // Success (('A', 'B'), "C")

run parseAThenB "ZBC" // Failure "Expecting 'A'. Got 'Z'"

run parseAThenB "AZC" // Failure "Expecting 'B'. Got 'Z'"

You can see that in the success case, the pair ('A', 'B') was returned, and also that failure

happens when either letter is missing from the input.

Let’s look at another important way of combining parsers – the “or else” combinator.

For example, say that we want a parser that matches “A” or “B”. How could we combine them?

The implementation logic would be:

- Run the first parser.

- On success, return the parsed value, along with the remaining input.

- Otherwise, on failure, run the second parser with the original input…

- …and in this case, return the result (success or failure) from the second parser.

Here’s the code for orElse:

let orElse parser1 parser2 =

let innerFn input =

// run parser1 with the input

let result1 = run parser1 input

// test the result for Failure/Success

match result1 with

| Success result ->

// if success, return the original result

result1

| Failure err ->

// if failed, run parser2 with the input

let result2 = run parser2 input

// return parser2's result

result2

// return the inner function

Parser innerFn

And we’ll define an infix version of orElse as well:

let ( <|> ) = orElse

If we look at the signature of orElse:

val orElse :

parser1:Parser<'a> -> parser2:Parser<'a> -> Parser<'a>

we can see that it works for any two parsers, but they must both be the same type 'a.

Time to test it. First, create the combined parser:

let parseA = pchar 'A'

let parseB = pchar 'B'

let parseAOrElseB = parseA <|> parseB

If you look at the types, you can see that all three values have type Parser<char>:

val parseA : Parser<char>

val parseB : Parser<char>

val parseAOrElseB : Parser<char>

Now if we run parseAOrElseB we can see that it successfully handles an “A” or a “B” as first character.

run parseAOrElseB "AZZ" // Success ('A', "ZZ")

run parseAOrElseB "BZZ" // Success ('B', "ZZ")

run parseAOrElseB "CZZ" // Failure "Expecting 'B'. Got 'C'"

With these two basic combinators, we can build more complex ones, such as “A and then (B or C)”.

Here’s how to build up aAndThenBorC from simpler parsers:

let parseA = pchar 'A'

let parseB = pchar 'B'

let parseC = pchar 'C'

let bOrElseC = parseB <|> parseC

let aAndThenBorC = parseA .>>. bOrElseC

And here it is in action:

run aAndThenBorC "ABZ" // Success (('A', 'B'), "Z")

run aAndThenBorC "ACZ" // Success (('A', 'C'), "Z")

run aAndThenBorC "QBZ" // Failure "Expecting 'A'. Got 'Q'"

run aAndThenBorC "AQZ" // Failure "Expecting 'C'. Got 'Q'"

Note that the last example gives a misleading error. It says “Expecting ‘C’” when it really should say “Expecting ‘B’ or ‘C’”. We won’t attempt to fix this right now, but in a later post we’ll implement better error messages.

This is where where the power of combinators starts kicking in, because with orElse in our toolbox, we can use it to build even more combinators. For example, let’s say that we want choose from a list of parsers, rather than just two.

Well, that’s easy. If we have a pairwise way of combining things, we can extend that to combining an entire list using reduce (for more on working with reduce, see this post on monoids ).

/// Choose any of a list of parsers

let choice listOfParsers =

List.reduce ( <|> ) listOfParsers

Note that this will fail if the input list is empty, but we will ignore that for now.

The signature of choice is:

val choice :

Parser<'a> list -> Parser<'a>

which shows us that, as expected, the input is a list of parsers, and the output is a single parser.

With choice available, we can create an anyOf parser that matches any character in a list, using the following logic:

- The input is a list of characters

- Each char in the list is transformed into a parser for that char using

pchar - Finally, all the parsers are combined using

choice

Here’s the code:

/// Choose any of a list of characters

let anyOf listOfChars =

listOfChars

|> List.map pchar // convert into parsers

|> choice // combine them

Let’s test it by creating a parser for any lowercase character and any digit character:

let parseLowercase =

anyOf ['a'..'z']

let parseDigit =

anyOf ['0'..'9']

If we test them, they work as expected:

run parseLowercase "aBC" // Success ('a', "BC")

run parseLowercase "ABC" // Failure "Expecting 'z'. Got 'A'"

run parseDigit "1ABC" // Success ("1", "ABC")

run parseDigit "9ABC" // Success ("9", "ABC")

run parseDigit "|ABC" // Failure "Expecting '9'. Got '|'"

Again, the error messages are misleading. Any lowercase letter can be expected, not just ‘z’, and any digit can be expected, not just ‘9’. As I said earlier, we’ll work on the error messages in a later post.

Let’s stop for now, and review what we have done:

- We have created a type

Parserthat is a wrapper for a parsing function. - The parsing function takes an input (e.g. string) and attempts to match the input using the criteria baked into the function.

- If the match succeeds, the parsing function returns a

Successwith the matched item and the remaining input. - If the match fails, the parsing function returns a

Failurewith reason for the failure. - And finally, we saw some “combinators” – ways in which

Parsers could be combined to make a newParser:andThenandorElseandchoice.

Here’s the complete listing for the parsing library so far – it’s about 90 lines of code.

Source code used in this post is available here.

open System

/// Type that represents Success/Failure in parsing

type ParseResult<'a> =

| Success of 'a

| Failure of string

/// Type that wraps a parsing function

type Parser<'T> = Parser of (string -> ParseResult<'T * string>)

/// Parse a single character

let pchar charToMatch =

// define a nested inner function

let innerFn str =

if String.IsNullOrEmpty(str) then

Failure "No more input"

else

let first = str.[0]

if first = charToMatch then

let remaining = str.[1..]

Success (charToMatch,remaining)

else

let msg = sprintf "Expecting '%c'. Got '%c'" charToMatch first

Failure msg

// return the "wrapped" inner function

Parser innerFn

/// Run a parser with some input

let run parser input =

// unwrap parser to get inner function

let (Parser innerFn) = parser

// call inner function with input

innerFn input

/// Combine two parsers as "A andThen B"

let andThen parser1 parser2 =

let innerFn input =

// run parser1 with the input

let result1 = run parser1 input

// test the result for Failure/Success

match result1 with

| Failure err ->

// return error from parser1

Failure err

| Success (value1,remaining1) ->

// run parser2 with the remaining input

let result2 = run parser2 remaining1

// test the result for Failure/Success

match result2 with

| Failure err ->

// return error from parser2

Failure err

| Success (value2,remaining2) ->

// combine both values as a pair

let newValue = (value1,value2)

// return remaining input after parser2

Success (newValue,remaining2)

// return the inner function

Parser innerFn

/// Infix version of andThen

let ( .>>. ) = andThen

/// Combine two parsers as "A orElse B"

let orElse parser1 parser2 =

let innerFn input =

// run parser1 with the input

let result1 = run parser1 input

// test the result for Failure/Success

match result1 with

| Success result ->

// if success, return the original result

result1

| Failure err ->

// if failed, run parser2 with the input

let result2 = run parser2 input

// return parser2's result

result2

// return the inner function

Parser innerFn

/// Infix version of orElse

let ( <|> ) = orElse

/// Choose any of a list of parsers

let choice listOfParsers =

List.reduce ( <|> ) listOfParsers

/// Choose any of a list of characters

let anyOf listOfChars =

listOfChars

|> List.map pchar // convert into parsers

|> choice

In this post, we have created the foundations of a parsing library, and few simple combinators.

In the next post, we’ll build on this to create a library with many more combinators.

- If you are interesting in using this technique in production, be sure to investigate the FParsec library for F#, which is optimized for real-world usage.

- For more information about parser combinators in general, search the internet for “Parsec”, the Haskell library that influenced FParsec (and this post).

- For some examples of using FParsec, try one of these posts:

Source code used in this post is available here.

Twitter

Twitter