Constraining capabilities based on identity and role

UPDATE: Slides and video from my talk on this topic

In the previous post, we started looking at “capabilities” as the basis for ensuring that code could not do any more than it was supposed to do. And I demonstrated this with a simple application that changed a configuration flag.

In this post, we’ll look at how to constrain capabilities based on the current user’s identity and role.

So let’s switch from the configuration example to a typical situation where stricter authorization is required.

Consider a website and call-centre with a backing database. We have the following security rules:

- A customer can only view or update their own record in the database (via the website)

- A call-centre operator can view or update any record in the database

This means that at some point, we’ll have to do some authorization based on the identity and role of the user. (We’ll assume that the user has been authenticated successfully).

The tendency in many web frameworks is to put the authorization in the UI layer, often in the controller. My concern about this approach is that once you are “inside” (past the gateway), any part of the app has full authority to access the database, and it is all to easy for code to do the wrong thing by mistake, resulting in a security breach.

Not only that, but because the authority is everywhere (“ambient”), it is hard to review the code for potential security issues.

To avoid these issues, let’s instead put the access logic as “low” as possible, in the database access layer in this case.

We’ll start with an obvious approach. We’ll add the identity and role to each database call and then do authorization there.

The following method assumes that there is a CustomerIdBelongsToPrincipal function that checks whether the customer id being accessed is owned by the principal requesting access.

Then, if the customerId does belong to the principal, or the principal has the role of “CustomerAgent”, the access is granted.

public class CustomerDatabase

{

public CustomerData GetCustomer(CustomerId id, IPrincipal principal)

{

if ( CustomerIdBelongsToPrincipal(id, principal) ||

principal.IsInRole("CustomerAgent") )

{

// get customer data

}

else

{

// throw authorization exception

}

}

}

Note that I have deliberately added the IPrincipal to the method signature – we are not allowing any “magic” where the principal is fetched from a global context.

As with the use of any global, having implicit access hides the dependencies and makes it hard to test in isolation.

Here’s the F# equivalent, using a Success/Failure return value rather than throwing exceptions:

let getCustomer id principal =

if customerIdBelongsToPrincipal id principal ||

principal.IsInRole("CustomerAgent")

then

// get customer data

Success "CustomerData"

else

Failure AuthorizationFailed

This “inline” authorization approach is all too common, but unfortunately it has many problems.

- It mixes up security concerns with the database logic. If the authorization logic gets more complicated, the code will also get more complicated.

- It throws an exception (C#) or returns an error (F#) if the authorization fails. It would be nice if we could tell in advance if we had the authorization rather than waiting until the last minute.

Let’s compare this with a capability-based approach. Instead of directly getting a customer, we first obtain the capability of doing it.

class CustomerDatabase

{

// "real" code is hidden from public view

private CustomerData GetCustomer(CustomerId id)

{

// get customer data

}

// Get the capability to call GetCustomer

public Func<CustomerId,CustomerData> GetCustomerCapability(CustomerId id, IPrincipal principal)

{

if ( CustomerIdBelongsToPrincipal(id, principal) ||

principal.IsInRole("CustomerAgent") )

{

// return the capability (the real method)

return GetCustomer;

}

else

{

// throw authorization exception

}

}

}

As you can see, if the authorization succeeds, a reference to the GetCustomer method is returned to the caller.

It might not be obvious, but the code above has a rather large security hole. I can request the capability for a particular customer id, but I get back a function that can called for any customer id! That’s not very safe, is it?

What we need to is “bake in” the customer id to the capability, so that it can’t be misused. The return value will now be a Func<CustomerData>, with the customer id not available

to be passed in any more.

class CustomerDatabase

{

// "real" code is hidden from public view

private CustomerData GetCustomer(CustomerId id)

{

// get customer data

}

// Get the capability to call GetCustomer

public Func<CustomerData> GetCustomerCapability(CustomerId id, IPrincipal principal)

{

if ( CustomerIdBelongsToPrincipal(id, principal) ||

principal.IsInRole("CustomerAgent") )

{

// return the capability (the real method)

return ( () => GetCustomer(id) );

}

else

{

// throw authorization exception

}

}

}

With this separation of concerns in place, we can now handle failure nicely, by returning an optional value which is present if we get the capability, or absent if not. That is, we know whether we have the capability at the time of trying to obtain it, not later on when we try to use it.

class CustomerDatabase

{

// "real" code is hidden from public view

// and doesn't need any checking of identity or role

private CustomerData GetCustomer(CustomerId id)

{

// get customer data

}

// Get the capability to call GetCustomer. If not allowed, return None.

public Option<Func<CustomerData>> GetCustomerCapability(CustomerId id, IPrincipal principal)

{

if (CustomerIdBelongsToPrincipal(id, principal) ||

principal.IsInRole("CustomerAgent"))

{

// return the capability (the real method)

return Option<Func<CustomerData>>.Some( () => GetCustomer(id) );

}

else

{

return Option<Func<CustomerData>>.None();

}

}

}

This assumes that we’re using some sort of Option type in C# rather than just returning null!

Finally, we can put the authorization logic into its own class (say CustomerDatabaseCapabilityProvider), to keep the authorization concerns separate from the CustomerDatabase.

We’ll have to find some way of keeping the “real” database functions private to all other callers though.

For now, I’ll just assume the database code is in a different assembly, and mark the code internal.

// not accessible to the business layer

internal class CustomerDatabase

{

// "real" code is hidden from public view

private CustomerData GetCustomer(CustomerId id)

{

// get customer data

}

}

// accessible to the business layer

public class CustomerDatabaseCapabilityProvider

{

CustomerDatabase _customerDatabase;

// Get the capability to call GetCustomer

public Option<Func<CustomerData>> GetCustomerCapability(CustomerId id, IPrincipal principal)

{

if (CustomerIdBelongsToPrincipal(id, principal) ||

principal.IsInRole("CustomerAgent"))

{

// return the capability (the real method)

return Option<Func<CustomerData>>.Some( () => _customerDatabase.GetCustomer(id) );

}

else

{

return Option<Func<CustomerData>>.None();

}

}

}

And here’s the F# version of the same code:

/// not accessible to the business layer

module internal CustomerDatabase =

let getCustomer (id:CustomerId) :CustomerData =

// get customer data

/// accessible to the business layer

module CustomerDatabaseCapabilityProvider =

// Get the capability to call getCustomer

let getCustomerCapability (id:CustomerId) (principal:IPrincipal) =

let principalId = GetIdForPrincipal(principal)

if (principalId = id) || principal.IsInRole("CustomerAgent") then

Some ( fun () -> CustomerDatabase.getCustomer id )

else

None

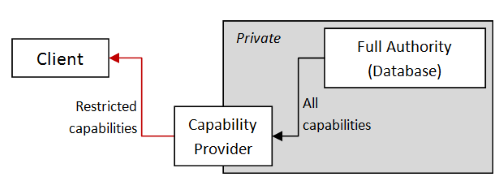

Here’s a diagram that represents this design:

Problems with this model

In this model, the caller is isolated from the CustomerDatabase, and the CustomerDatabaseCapabilityProvider acts as a proxy between them.

Which means, as currently designed, for every function available in CustomerDatabase there must be a parallel function available in CustomerDatabaseCapabilityProvider as well.

We can see that this approach will not scale well.

It would be nice if we had a way to generally get capabilities for a whole set of database functions rather than one at a time. Let’s see if we can do that!

The getCustomer function in CustomerDatabase can be thought of as a capability with no restrictions, while the getCustomerCapability

returns a capability restricted by identity and role.

But note that the two function signatures are similar (CustomerId -> CustomerData vs unit -> CustomerData), and so they are almost interchangeable from the callers point of view.

In a sense, then, the second capability is a transformed version of the first, with additional restrictions.

Transforming functions to new functions! This is something we can easily do.

So, let’s write a transformer that, given any function of type CustomerId -> 'a, we return a function with the customer id baked in (unit -> 'a),

but only if the authorization requirements are met.

module CustomerCapabilityFilter =

// Get the capability to use any function that has a CustomerId parameter

// but only if the caller has the same customer id or is a member of the

// CustomerAgent role.

let onlyForSameIdOrAgents (id:CustomerId) (principal:IPrincipal) (f:CustomerId -> 'a) =

let principalId = GetIdForPrincipal(principal)

if (principalId = id) || principal.IsInRole("CustomerAgent") then

Some (fun () -> f id)

else

None

The type signature for the onlyForSameIdOrAgents function is (CustomerId -> 'a) -> (unit -> 'a) option. It accepts any CustomerId based function

and returns, maybe, the same function with the customer id already applied if the authorization succeeds. If the authorization does not succeed, None is returned instead.

You can see that this function will work generically with any function that has a CustomerId as the first parameter. That could be “get”, “update”, “delete”, etc.

So for example, given:

module internal CustomerDatabase =

let getCustomer (id:CustomerId) =

// get customer data

let updateCustomer (id:CustomerId) (data:CustomerData) =

// update customer data

We can create restricted versions now, for example at the top level bootstrapper or controller:

let principal = // from context

let id = // from context

// attempt to get the capabilities

let getCustomerOnlyForSameIdOrAgents =

onlyForSameIdOrAgents id principal CustomerDatabase.getCustomer

let updateCustomerOnlyForSameIdOrAgents =

onlyForSameIdOrAgents id principal CustomerDatabase.updateCustomer

The types of getCustomerOnlyForSameIdOrAgents and updateCustomerOnlyForSameIdOrAgents are similar to the original functions in the database module,

but with CustomerId replaced with unit:

val getCustomerOnlyForSameIdOrAgents :

(unit -> CustomerData) option

val updateCustomerOnlyForSameIdOrAgents :

(unit -> CustomerData -> unit) option

The updateCustomerOnlyForSameIdOrAgents has a extra CustomerData parameter, so the extra unit where the CustomerId used to be is a bit ugly.

If this is too annoying, you could easily create other versions of the function which handle this more elegantly. I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader!

So now we have an option value that might or might not contain the capability we wanted. If it does, we can create a child component and pass in the capability. If it does not, we can return some sort of error, or hide a element from a view, depending on the type of application.

match getCustomerOnlyForSameIdOrAgents with

| Some cap -> // create child component and pass in the capability

| None -> // return error saying that you don't have the capability to get the data

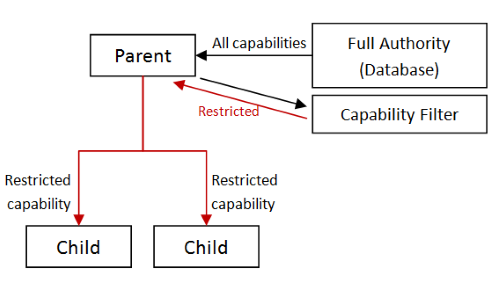

Here’s a diagram that represents this design:

Because capabilities are functions, we can easily create new capabilities by chaining or combining transformations.

For example, we could create a separate filter function for each business rule, like this:

module CustomerCapabilityFilter =

let onlyForSameId (id:CustomerId) (principal:IPrincipal) (f:CustomerId -> 'a) =

if customerIdBelongsToPrincipal id principal then

Some (fun () -> f id)

else

None

let onlyForAgents (id:CustomerId) (principal:IPrincipal) (f:CustomerId -> 'a) =

if principal.IsInRole("CustomerAgent") then

Some (fun () -> f id)

else

None

For the first business rule, onlyForSameId, we return a capability with the customer id baked in, as before.

The second business rule, onlyForAgents, doesn’t mention customer ids anywhere, so why do we restrict the function parameter to CustomerId -> 'a?

The reason is that it enforces that this rule only applies to customer centric capabilities, not ones relating to products or payments, say.

But now, to make the output of this filter compatible with the first rule (unit -> 'a), we need to pass in a customer id and partially apply it too.

It’s a bit of a hack but it will do for now.

We can also write a generic combinator that returns the first valid capability from a list.

// given a list of capability options,

// return the first good one, if any

let first capabilityList =

capabilityList |> List.tryPick id

It’s a trivial implementation really – this is the kind of helper function that is just to help the code be a little more self-documenting.

With this in place, we can apply the rules separately, take the two filters and combine them into one.

let getCustomerOnlyForSameIdOrAgents =

let f = CustomerDatabase.getCustomer

let cap1 = onlyForSameId id principal f

let cap2 = onlyForAgents id principal f

first [cap1; cap2]

// val getCustomerOnlyForSameIdOrAgents : (CustomerId -> CustomerData) option

Or let’s say we have some sort of restriction; the operation can only be performed during business hours, say.

let onlyIfDuringBusinessHours (time:DateTime) f =

if time.Hour >= 8 && time.Hour <= 17 then

Some f

else

None

We can write another combinator that restricts the original capability. This is just a version of “bind”.

// given a capability option, restrict it

let restrict filter originalCap =

originalCap

|> Option.bind filter

With this in place, we can restrict the “agentsOnly” capability to business hours:

let getCustomerOnlyForAgentsInBusinessHours =

let f = CustomerDatabase.getCustomer

let cap1 = onlyForAgents id principal f

let restriction f = onlyIfDuringBusinessHours (DateTime.Now) f

cap1 |> restrict restriction

So now we have created a new capability, “Customer agents can only access customer data during business hours”, which tightens the data access logic a bit more.

We can combine this with the previous onlyForSameId filter to build a compound capability which can access customer data:

- if you have the same customer id (at any time of day)

- if you are a customer agent (only during business hours)

let getCustomerOnlyForSameId =

let f = CustomerDatabase.getCustomer

onlyForSameId id principal f

let getCustomerOnlyForSameId_OrForAgentsInBusinessHours =

let cap1 = getCustomerOnlyForSameId

let cap2 = getCustomerOnlyForAgentsInBusinessHours

first [cap1; cap2]

As you can see, this approach is a useful way to build complex capabilities from simpler ones.

It should be obvious that you can easily create additional transforms which can extend capabilities in other ways. Some examples:

- a capability that writes to an audit log on each execution.

- a capability that can only be performed once.

- a capability that can be revoked when needed.

- a capability that is throttled and can only be performed a limited number of times in a given time period (such as password change attempts).

And so on.

Here are implementations of the first three of them:

/// Uses of the capability will be audited

let auditable capabilityName f =

fun x ->

// simple audit log!

printfn "AUDIT: calling %s with %A" capabilityName x

// use the capability

f x

/// Allow the function to be called once only

let onlyOnce f =

let allow = ref true

fun x ->

if !allow then //! is dereferencing not negation!

allow := false

f x

else

Failure OnlyAllowedOnce

/// Return a pair of functions: the revokable capability,

/// and the revoker function

let revokable f =

let allow = ref true

let capability = fun x ->

if !allow then //! is dereferencing not negation!

f x

else

Failure Revoked

let revoker() =

allow := false

capability, revoker

Let’s say that we have an updatePassword function, such as this:

module internal CustomerDatabase =

let updatePassword (id,password) =

Success "OK"

We can then create a auditable version of updatePassword:

let updatePasswordWithAudit x =

auditable "updatePassword" CustomerDatabase.updatePassword x

And then test it:

updatePasswordWithAudit (1,"password")

updatePasswordWithAudit (1,"new password")

The results are:

AUDIT: calling updatePassword with (1, "password")

AUDIT: calling updatePassword with (1, "new password")

Or, we could create a one-time only version:

let updatePasswordOnce =

onlyOnce CustomerDatabase.updatePassword

And then test it:

updatePasswordOnce (1,"password") |> printfn "Result 1st time: %A"

updatePasswordOnce (1,"password") |> printfn "Result 2nd time: %A"

The results are:

Result 1st time: Success "OK"

Result 2nd time: Failure OnlyAllowedOnce

Finally, we can create a revokable function:

let revokableUpdatePassword, revoker =

revokable CustomerDatabase.updatePassword

And then test it:

revokableUpdatePassword (1,"password") |> printfn "Result 1st time before revoking: %A"

revokableUpdatePassword (1,"password") |> printfn "Result 2nd time before revoking: %A"

revoker()

revokableUpdatePassword (1,"password") |> printfn "Result 3nd time after revoking: %A"

With the following results:

Result 1st time before revoking: Success "OK"

Result 2nd time before revoking: Success "OK"

Result 3nd time after revoking: Failure Revoked

The code for all these F# examples is available as a gist here.

Here’s the code to a complete application in F# (also available as a gist here).

This example consists of a simple console app that allows you to get and update customer records.

- The first step is to login as a user. “Alice” and “Bob” are normal users, while “Zelda” has a customer agent role.

- Once logged in, you can select a customer to edit. Again, you are limited to a choice between “Alice” and “Bob”. (I’m sure you can hardly contain your excitement)

- Once a customer is selected, you are presented with some (or none) of the following options:

- Get a customer’s data.

- Update a customer’s data.

- Update a customer’s password.

Which options are shown depend on which capabilities you have. These in turn are based on who you are logged in as, and which customer is selected.

We’ll start with the core domain types that are shared across the application:

module Domain =

open Rop

type CustomerId = CustomerId of int

type CustomerData = CustomerData of string

type Password = Password of string

type FailureCase =

| AuthenticationFailed of string

| AuthorizationFailed

| CustomerNameNotFound of string

| CustomerIdNotFound of CustomerId

| OnlyAllowedOnce

| CapabilityRevoked

The FailureCase type documents all possible things that can go wrong at the top-level of the application. See the “Railway Oriented Programming” talk for more discussion on this.

Next, we document all the capabilities that are available in the application. To add clarity to the code, each capability is given a name (i.e. a type alias).

type GetCustomerCap = unit -> SuccessFailure<CustomerData,FailureCase>

Finally, the CapabilityProvider is a record of functions, each of which accepts a customer id and principal, and returns an optional capability of the specified type.

This record is created in the top level model and then passed around to the child components.

Here’s the complete code for this module:

module Capabilities =

open Rop

open Domain

// capabilities

type GetCustomerCap = unit -> SuccessFailure<CustomerData,FailureCase>

type UpdateCustomerCap = unit -> CustomerData -> SuccessFailure<unit,FailureCase>

type UpdatePasswordCap = Password -> SuccessFailure<unit,FailureCase>

type CapabilityProvider = {

/// given a customerId and IPrincipal, attempt to get the GetCustomer capability

getCustomer : CustomerId -> IPrincipal -> GetCustomerCap option

/// given a customerId and IPrincipal, attempt to get the UpdateCustomer capability

updateCustomer : CustomerId -> IPrincipal -> UpdateCustomerCap option

/// given a customerId and IPrincipal, attempt to get the UpdatePassword capability

updatePassword : CustomerId -> IPrincipal -> UpdatePasswordCap option

}

This module references a SuccessFailure result type similar to the one discussed here, but which I won’t show.

Next, we’ll roll our own little authentication system. Note that when the user “Zelda” is authenticated, the role is set to “CustomerAgent”.

module Authentication =

open Rop

open Domain

let customerRole = "Customer"

let customerAgentRole = "CustomerAgent"

let makePrincipal name role =

let iden = GenericIdentity(name)

let principal = GenericPrincipal(iden,[|role|])

principal :> IPrincipal

let authenticate name =

match name with

| "Alice" | "Bob" ->

makePrincipal name customerRole |> Success

| "Zelda" ->

makePrincipal name customerAgentRole |> Success

| _ ->

AuthenticationFailed name |> Failure

let customerIdForName name =

match name with

| "Alice" -> CustomerId 1 |> Success

| "Bob" -> CustomerId 2 |> Success

| _ -> CustomerNameNotFound name |> Failure

let customerIdOwnedByPrincipal customerId (principle:IPrincipal) =

principle.Identity.Name

|> customerIdForName

|> Rop.map (fun principalId -> principalId = customerId)

|> Rop.orElse false

The customerIdForName function attempts to find the customer id associated with a particular name,

while the customerIdOwnedByPrincipal compares this id with another one.

Here are the functions related to authorization, very similar to what was discussed above.

module Authorization =

open Rop

open Domain

let onlyForSameId (id:CustomerId) (principal:IPrincipal) (f:CustomerId -> 'a) =

if Authentication.customerIdOwnedByPrincipal id principal then

Some (fun () -> f id)

else

None

let onlyForAgents (id:CustomerId) (principal:IPrincipal) (f:CustomerId -> 'a) =

if principal.IsInRole(Authentication.customerAgentRole) then

Some (fun () -> f id)

else

None

let onlyIfDuringBusinessHours (time:DateTime) f =

if time.Hour >= 8 && time.Hour <= 17 then

Some f

else

None

// constrain who can call a password update function

let passwordUpdate (id:CustomerId) (principal:IPrincipal) (f:CustomerId*Password -> 'a) =

if Authentication.customerIdOwnedByPrincipal id principal then

Some (fun password -> f (id,password))

else

None

// return the first good capability, if any

let first capabilityList =

capabilityList |> List.tryPick id

// given a capability option, restrict it

let restrict filter originalCap =

originalCap

|> Option.bind filter

/// Uses of the capability will be audited

let auditable capabilityName principalName f =

fun x ->

// simple audit log!

let timestamp = DateTime.UtcNow.ToString("u")

printfn "AUDIT: User %s used capability %s at %s" principalName capabilityName timestamp

// use the capability

f x

/// Return a pair of functions: the revokable capability,

/// and the revoker function

let revokable f =

let allow = ref true

let capability = fun x ->

if !allow then //! is dereferencing not negation!

f x

else

Failure CapabilityRevoked

let revoker() =

allow := false

capability, revoker

The functions related to database access are similar to those in the earlier examples, only this time we have implemented a crude in-memory database (just a Dictionary).

module CustomerDatabase =

open Rop

open System.Collections.Generic

open Domain

let private db = Dictionary<CustomerId,CustomerData>()

let getCustomer id =

match db.TryGetValue id with

| true, value -> Success value

| false, _ -> Failure (CustomerIdNotFound id)

let updateCustomer id data =

db.[id] <- data

Success ()

let updatePassword (id:CustomerId,password:Password) =

Success () // dummy implementation

Next we have the “business services” (for lack of better word) where all the work gets done.

module BusinessServices =

open Rop

open Domain

// use the getCustomer capability

let getCustomer capability =

match capability() with

| Success data -> printfn "%A" data

| Failure err -> printfn ".. %A" err

// use the updateCustomer capability

let updateCustomer capability =

printfn "Enter new data: "

let customerData = Console.ReadLine() |> CustomerData

match capability () customerData with

| Success _ -> printfn "Data updated"

| Failure err -> printfn ".. %A" err

// use the updatePassword capability

let updatePassword capability =

printfn "Enter new password: "

let password = Console.ReadLine() |> Password

match capability password with

| Success _ -> printfn "Password updated"

| Failure err -> printfn ".. %A" err

Note that each of these functions is passed in only the capability needed to do its job. This code knows nothing about databases, or anything else.

Yes, in this crude example, the code is reading and writing directly to the console. Obviously in a more complex (and less crude!) design, the inputs to these functions would be passed in as parameters.

Here’s a simple exercise: replace the direct access to the console with a capability such as getDataWithPrompt?

Now for the user interface module, where most of the complex code lies.

First up is a type (CurrentState) that represents the state of the user interface.

- When we’re

LoggedOutthere is noIPrincipalavailable. - When we’re

LoggedInthere is aIPrincipalavailable, but no selected customer. - When we’re in the

CustomerSelectedstate there is both aIPrincipaland aCustomerIdavailable. - Finally, the

Exitstate is a signal to the app to shutdown.

I very much like using a “state” design like this, because it ensures that we can’t accidentally access data that we shouldn’t. For example, we literally cannot access a customer when none is selected, because there is no customer id in that state!

For each state, there is a corresponding function.

loggedOutActions is run when we are in the LoggedOut state. It presents the available actions to you, and changes the state accordingly.

You can log in as a user, or exit. If the login is successful (authenticate name worked) then the state is changed to LoggedIn.

loggedInActions is run when we are in the LoggedIn state. You can select a customer, or log out.

If the customer selection is successful (customerIdForName customerName worked) then the state is changed to CustomerSelected.

selectedCustomerActions is run when we are in the CustomerSelected state. This works as follows:

- First, find out what capabilities we have.

- Next convert each capability into a corresponding menu text (using

Option.mapbecause the capability might be missing), then remove the ones that are None. - Next, read a line from input, and depending on what it is, call one of the “business services” (

getCustomer,updateCustomer, orupdatePassword).

Finally the mainUiLoop function loops around until the state is set to Exit.

module UserInterface =

open Rop

open Domain

open Capabilities

type CurrentState =

| LoggedOut

| LoggedIn of IPrincipal

| CustomerSelected of IPrincipal * CustomerId

| Exit

/// do the actions available while you are logged out. Return the new state

let loggedOutActions originalState =

printfn "[Login] enter Alice, Bob, Zelda, or Exit: "

let action = Console.ReadLine()

match action with

| "Exit" ->

// Change state to Exit

Exit

| name ->

// otherwise try to authenticate the name

match Authentication.authenticate name with

| Success principal ->

LoggedIn principal

| Failure err ->

printfn ".. %A" err

originalState

/// do the actions available while you are logged in. Return the new state

let loggedInActions originalState (principal:IPrincipal) =

printfn "[%s] Pick a customer to work on. Enter Alice, Bob, or Logout: " principal.Identity.Name

let action = Console.ReadLine()

match action with

| "Logout" ->

// Change state to LoggedOut

LoggedOut

// otherwise treat it as a customer name

| customerName ->

// Attempt to find customer

match Authentication.customerIdForName customerName with

| Success customerId ->

// found -- change state

CustomerSelected (principal,customerId)

| Failure err ->

// not found -- stay in originalState

printfn ".. %A" err

originalState

let getAvailableCapabilities capabilityProvider customerId principal =

let getCustomer = capabilityProvider.getCustomer customerId principal

let updateCustomer = capabilityProvider.updateCustomer customerId principal

let updatePassword = capabilityProvider.updatePassword customerId principal

getCustomer,updateCustomer,updatePassword

/// do the actions available when a selected customer is available. Return the new state

let selectedCustomerActions originalState capabilityProvider customerId principal =

// get the individual component capabilities from the provider

let getCustomerCap,updateCustomerCap,updatePasswordCap =

getAvailableCapabilities capabilityProvider customerId principal

// get the text for menu options based on capabilities that are present

let menuOptionTexts =

[

getCustomerCap |> Option.map (fun _ -> "(G)et");

updateCustomerCap |> Option.map (fun _ -> "(U)pdate");

updatePasswordCap |> Option.map (fun _ -> "(P)assword");

]

|> List.choose id

// show the menu

let actionText =

match menuOptionTexts with

| [] -> " (no other actions available)"

| texts -> texts |> List.reduce (fun s t -> s + ", " + t)

printfn "[%s] (D)eselect customer, %s" principal.Identity.Name actionText

// process the user action

let action = Console.ReadLine().ToUpper()

match action with

| "D" ->

// revert to logged in with no selected customer

LoggedIn principal

| "G" ->

// use Option.iter in case we don't have the capability

getCustomerCap

|> Option.iter BusinessServices.getCustomer

originalState // stay in same state

| "U" ->

updateCustomerCap

|> Option.iter BusinessServices.updateCustomer

originalState

| "P" ->

updatePasswordCap

|> Option.iter BusinessServices.updatePassword

originalState

| _ ->

// unknown option

originalState

let rec mainUiLoop capabilityProvider state =

match state with

| LoggedOut ->

let newState = loggedOutActions state

mainUiLoop capabilityProvider newState

| LoggedIn principal ->

let newState = loggedInActions state principal

mainUiLoop capabilityProvider newState

| CustomerSelected (principal,customerId) ->

let newState = selectedCustomerActions state capabilityProvider customerId principal

mainUiLoop capabilityProvider newState

| Exit ->

() // done

let start capabilityProvider =

mainUiLoop capabilityProvider LoggedOut

With all this in place, we can implement the top-level module.

This module fetches all the capabilities, adds restrictions as explained previously, and creates a capabilities record.

The capabilities record is then passed into the user interface when the app is started.

module Application=

open Rop

open Domain

open CustomerDatabase

open Authentication

open Authorization

let capabilities =

let getCustomerOnlyForSameId id principal =

onlyForSameId id principal CustomerDatabase.getCustomer

let getCustomerOnlyForAgentsInBusinessHours id principal =

let f = CustomerDatabase.getCustomer

let cap1 = onlyForAgents id principal f

let restriction f = onlyIfDuringBusinessHours (DateTime.Now) f

cap1 |> restrict restriction

let getCustomerOnlyForSameId_OrForAgentsInBusinessHours id principal =

let cap1 = getCustomerOnlyForSameId id principal

let cap2 = getCustomerOnlyForAgentsInBusinessHours id principal

first [cap1; cap2]

let updateCustomerOnlyForSameId id principal =

onlyForSameId id principal CustomerDatabase.updateCustomer

let updateCustomerOnlyForAgentsInBusinessHours id principal =

let f = CustomerDatabase.updateCustomer

let cap1 = onlyForAgents id principal f

let restriction f = onlyIfDuringBusinessHours (DateTime.Now) f

cap1 |> restrict restriction

let updateCustomerOnlyForSameId_OrForAgentsInBusinessHours id principal =

let cap1 = updateCustomerOnlyForSameId id principal

let cap2 = updateCustomerOnlyForAgentsInBusinessHours id principal

first [cap1; cap2]

let updatePasswordOnlyForSameId id principal =

let cap = passwordUpdate id principal CustomerDatabase.updatePassword

cap

|> Option.map (auditable "UpdatePassword" principal.Identity.Name)

// create the record that contains the capabilities

{

getCustomer = getCustomerOnlyForSameId_OrForAgentsInBusinessHours

updateCustomer = updateCustomerOnlyForSameId_OrForAgentsInBusinessHours

updatePassword = updatePasswordOnlyForSameId

}

let start() =

// pass capabilities to UI

UserInterface.start capabilities

The complete code for this example is available as a gist here.

In part 2, we added authorization and other transforms as a separate concern that could be applied to restrict authority. Again, there is nothing particularly clever about using functions like this, but I hope that this has given you some ideas that might be useful.

Question: Why go to all this trouble? What’s the benefit over just testing an “IsAuthorized” flag or something?

Here’s a typical use of a authorization flag:

if user.CanUpdate() then

doTheAction()

Recall the quote from the previous post: “Capabilities should ‘fail safe’. If a capability cannot be obtained, or doesn’t work, we must not allow any progress on paths that assumed that it was successful.”

The problem with testing a flag like this is that it’s easy to forget, and the compiler won’t complain if you do. And then you have a possible security breach, as in the following code.

if user.CanUpdate() then

// ignore

// now do the action anyway!

doTheAction()

Not only that, but by “inlining” the test like this, we’re mixing security concerns into our main code, as pointed out earlier.

In contrast, a simple capability approach looks like this:

let updateCapability = // attempt to get the capability

match updateCapability with

| Some update -> update() // call the function

| None -> () // can't call the function

In this example, it is not possible to accidentally use the capability if you are not allowed to, as you literally don’t have a function to call! And this has to be handled at compile-time, not at runtime.

Furthermore, as we have just seen, capabilities are just functions, so we get all the benefits of filtering, etc., which are not available with the inlined boolean test version.

Question: In many situations, you don’t know whether you can access a resource until you try. So aren’t capabilities just extra work?

This is indeed true. For example, you might want to test whether a file exists first, and only then try to access it. The IT gods are always ruthless in these cases, and in the time between checking the file’s existence and trying to open it, the file will probably be deleted!

So since we will have to check for exceptions anyway, why do two slow I/O operations when one would have sufficed?

The answer is that the capability model is not about physical or system-level authority, but logical authority – only having the minimum you need to accomplish a task.

For example, a web service process may be operating at a high level of system authority, and can access any database record. But we don’t want to expose that to most of our code. We want to make sure that any failures in programming logic cannot accidentally expose unauthorized data.

Yes, of course, the capability functions themselves must do error handling,

and as you can see in the snippets above, I’m using the Success/Failure result type as described here.

As a result, we will need to merge failures from core functions (e.g. database errors) with capability-specific failures such as Failure OnlyAllowedOnce.

Question: You’ve created a whole module with types defined for each capability. I might have hundreds of capabilities. Do you really expect me to do all this extra work?

There are two points here, so let’s address each one in turn:

First, do you have a system that already uses fine-grained authorization, or has business-critical requirements about not leaking data, or performing actions in an unauthorized context, or needs a security audit?

If none of these apply, then indeed, this approach is complete overkill!

But if you do have such a system, that raises some new questions:

- should the capabilities that are authorized be explicitly described in the code somewhere?

- and if so, should the capabilities be explicit throughout the code, or only at the top-level (e.g. in the controller) and implicit everywhere else.

The question comes to down to whether you want to be explicit or implicit.

Personally, I prefer things like this to be explicit. It may be a little extra work initially, just a few lines to define each capability, but I find that it generally stops problems from occurring further down the line.

And it has the benefit of acting as a single place to document all the security-related capabilities that you support. Any new requirements would require a new entry here, so can be sure that no capabilities can sneak in under the radar (assuming developers follow these practices).

Question: In this code, you’ve rolled your own authorization. Wouldn’t you use a proper authorization provider instead?

Yes. This code is just an example. The authorization logic is completely separate from the domain logic, so it should be easy to substitute any authorization provider, such as

ClaimsAuthorizationManager class, or something like

XACML.

I’ve got more questions…

If you missed them, some additional questions are answered at the end of part 1. Otherwise please add your question in the comments below, and I’ll try to address it.

In the next post, we’ll look at how to use types to emulate access tokens and prevent unauthorized access to global functions.

NOTE: All the code for this post is available as a gist here and here.

Twitter

Twitter